Island Chronicles, vol. 12: ‘Well, I have visited the Slaver’ – May H. Stacey’s Account of the Slave Ship Wildfire at Key West, 1860

An examination and transcript of a letter in the FKHC collection

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

Introduction

On May 2, 1860, on board the US Navy Steamer Crusader[1] in Key West Harbor, Master’s Mate May H. Stacey began a letter to his father, Davis B. Stacey of Chester, Pennsylvania.[2] The Crusader was one of four Navy steamers – Mohawk, Wyandotte, Crusader, and Water Witch – that had been ordered in September of 1859 to patrol the coast of Cuba to stop the participation of US-flagged vessels in the illegal slave trade. With an increase in the labor needs of the Cuban sugar industry, a business that had long depended on enslaved laborers, many American ship owners found they could make tremendous sums of money by transporting captive West African people to the island and selling them. The US Navy ships patrolled the north and south coasts of Cuba and intercepted suspicious-looking vessels. If they were found to be American-owned slave ships, the vessels were seized, and the crews arrested. Any Africans rescued in the effort became “recaptives,” or refugee wards of the U.S. government.

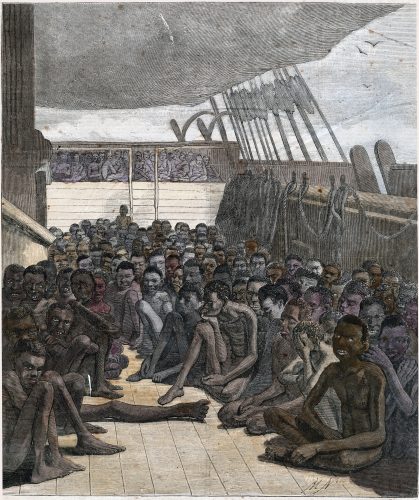

When Stacey wrote his letter, Crusader was suffering from mechanical issues – its “port sylinder had been busted” on April 30 – and the vessel was forced to come to Key West for repairs. As engineers sought a fix for the steamer’s engine, another Navy vessel, the USS Mohawk, came into port with a captured slave ship. On April 26, Mohawk had encountered the bark Wildfire in the Old Bahama Channel, along the northeast coast of Cuba. When Wildfire was boarded and found to have captive Africans on board, it was seized and taken under tow. On April 30, Mohawk arrived at Key West with the prize and delivered 507 Africans to U.S. Marshal Fernando Moreno. The arrival of the large group was a surprise to everyone at Key West, and the Africans were kept onboard Wildfire by the Marshal until shoreside accommodations could be built for them.

Of course, the arrival of ship full of hundreds of people, many sick, and all in need of food, water, and clothing, was a significant event, but because these people were native Africans, people not typically encountered by those in the States, their arrival was also a spectacle. May Stacey visited the Wildfire, and his report to his father on what he saw is a rare firsthand account of the conditions of a slave ship and the sufferings of its victims.

Stacey was sympathetic as he reported on the poor health of the people and the cruel, cramped spaces they had been allotted on the ship. As he described it, many of the rescued people were very sick and unlikely to survive. But he also gave mean, racist descriptions of the Africans, noting they smelled bad, and their language sounded like “the concert of a thousand monkeys.” Most shockingly, though, Stacey stooped to cruel victim blaming when he asserted that the squalid state of the Africans onboard Wildfire was somehow proof that slavery, either in the U.S. or Cuba, would have been better for them than their “savage liberty.” It is a perplexing and troubling statement, particularly because it came from someone tasked with stopping the slave trade. Stacey’s negative tone did seem to ameliorate a bit, though, when he later visited the Africans at their new quarters, and he saw their condition had improved.

Wildfire’s crew was also brought ashore, and most were jailed, but May Stacey was able to visit those who were sick and hospitalized, and he gleaned information from them that sheds light on the mechanics of the slave ship’s voyage. Wildfire first sailed from New York for Africa under an American captain and with a cargo of cloth. The crew sold or traded the cloth at the Congo River, transactions that allowed them to acquire a cargo of people. The voyage to Cuba was then made under a Spanish captain who had initially sailed as a passenger. The crewmen said they had hoped to acquire 1,000 people, but the fear of getting caught pressured them to leave. Each of the working men on Wildfire was to be paid $800 for the voyage.

Today, May Stacey’s experiences with the Wildfire and its people give us historical insight. For him, though, the events were foretelling. Despite his hope that Crusader’s mechanical issues might be so bad that it would have to be sent northward for repairs (allowing him an escape from the looming summer heat) the steamer was patched up and continued its patrol of the Cuban coast. On May 23, along the island’s northeast shore, the crew of the Crusader captured the American slaver Bogota. They brought the prize, with over 400 Africans on board, to Key West.

The Letter

The transcript of May H. Stacey’s letter, with the original spelling and grammar.

Crusader May 2nd 1860 Key West

My Dear Father –

Key West again! Our errant here is however very different from what it has been heretofore. On the very last day of April, while steaming along on a NNW course course to the Eastward of Sagua La Grande and near the Southern edge of the banks, about five o’clock in the evening I heard three thumps and the Engines stopped. After a time the chief Engineer reported that the port sylinder had been busted. This accident was occasioned by the breaking of one of the piston head bolts and the head of it (the bolt) falling down came in contact with the sylinder head and busted it right off. Sail was immediately made, and while the engineers where engaged disconnecting the Port Engine, the Capt held a consultation with his officers and it was determined to bear up for this port under one Engine. Accordingly at Eight o’clock the helm was put up, and we came here. The wind was favorable the whole way and our passage was not a long one. A board consisting of the chief Engineers of the Mohawk, Wyandotte, & Crusader is now examining the injury

p.2

and I will acquaint you with their opinion. It is thought that the damage can be repaired sufficiently to enable us to continue the cruise; otherwise we shall make the best of the way to one of our Navy yards and have a new sylinder put in. Thank the Lord it is not possible to do a job of this kind at Pensacola, and it will be necessary to go to Norfolk, Phila, New York or Boston. I don’t wish the ship any harm but I do hope that the Engine cannot be repaired short of one of these ports. If we go to the north it will take two or three months to make a new sylinder, thus the hurricane season will be over, and should I return to this ship, I would miss much hot disagreeable weather, and besides that have the unbounded pleasure of seeing you all at home, which is the most important consideration of all.

I have before intimated that the Mohawk is in this port, and the best of it is she is not alone but has lying under her quarter a most beautiful barque called the “Fire Fly,” having on board upwards of five hundred negroes just from the coast of Africa.[3] She was captured in a calm off Nuevitas about three days ago, and brought in. I am at this moment about to visit her, and when I return will give you an account of my visit.

p.3

Well, I have visited the Slaver. It was a sight which those who have not seen can form no idea of whatever. It was disgusting to all the senses. In the first place your nose was offended at an infernal stench that pervaded the craft throughout; your ears were filled with a chatter that resembled more the concert of a thousand monkeys than the language of human beings. And now for the eye. As we came alongside perhaps eighteen or twenty woolly heads creeted us, and upon ascending the side ladder we observed perhaps an hundred & fifty little black children lying about, & standing around the greater portion in a state of absolute nakedness. The women who occupied the cabin were ordered on deck for our gratification and it was an horrible sight to see the poor creatures, in all stages of amaciation, make their appearance. A glance on the slave deck was enough to fill the mind with indiscernable horror at the thought of what the poor creatures must have suffered in twenty eight days passage. The deck was constructed of rough unplaned planks and raised from the ship’s bottom about three feet leaving a space of about four feet in height and extending fore & aft. In this

p.4

the little fellows were huddled together. Thirty four are ashore at present sick and will probably die. I noticed one little black boy lying on deck, perfectly naked, and apparently too unwell to move hand nor foot. He only cast imploring glances about too expressive to be misunderstood; but no one paid any attention to them. It was altogether horrible beyond description. The “Fire Fly” is a barque of about four hundred tons, evidently built with an eye to speed. She has a beautiful bow, and run; her spars are very tall, and her yards unusually square. She has twenty thousand dollars concealed somewhere about her, but thus far the officers of the Mohawk have not been able to discover it.

Bah! The smell of the infernal n____s is in my nose yet. I wish some of the northern abolitionists could just step aboard the “Fire Fly.” I do not think they would think the slave trade such an evil. Why one of our negroes in the south is a thousand times better off as a slave than these creatures possibly can be in all their savage liberty. The mode of transportation is dreadful, but their lots afterwards, even under the tyrannical spaniards, is better than their native wildness.

p.5

I will just mention that the condition of these wretches has been much ameliorated since the capture. They are permitted to come on deck, and are obliged to keep themselves somewhat clean. Tomorrow they are to be landed at Key West. I suppose the vessel will be sold, and together with the government allowance of twenty five dollars a head to the captors, the “Mohawk” will make considerable prize money.[4] We know of three vessels at this time expected on the coast of Cuba, and regret that, just at this time we are “hors de combat.”[5] It is reported that two large steamers with each 12 hundred on board are at this time on the way to the coast of Cuba, besides a number of smaller vessels. There is prize money for somebody in the wind.

Several days must elapse before I can send this, and in the meanwhile I will make such additions to this letter as I think may interest you.

p.6

Our Capt is one of the liveliest fellows in the world, and immediately fond of company.[6] He is desidedly Epicurean in his tastes. To night we are to have a grand shin dig on board. The Crusader is a universal favorite among the ladies wherever we go, but particularly at Key West, while on the other hand the men are not at all friendly. I presume they are jealous.[7]

These parties on ship board are the abomination of all first Lieutenants, but particularly of our executive officer who is a plain rough man and is not fond of society. He has all the trouble with none of the pleasure.

I don’t think it possible for a ship to be more musical than ours. From morning until night we hear nothing but grand solos, polka’s, waltzs, songs, negro minstrels, +c. She ought to be a very happy ship, but the men grumble a good deal. This may be attributable to a variety of causes.

This letter is becoming a thing of thread + patches. Every day I find something to add. Yesterday I visited the house constructed for the accommodation of the slaves. They have all been turned over to the U.S. Marshall and he has built a place for them. It is not such a mansion as would satisfy either you nor I, but I dare say they esteem it a very fine place.[8] You

p.7

would be astonished to observe the very marked change in their appearance. They look at least an hundred times better. All the men have their teeth filed and they look like fangs.[9]

A very remarkable thing about these negroes is their power of repeating. You say something to them and they will repeat it word for word with the greatest distinction.

I visited also the sick. Some of them are coming on very well, while others will never recover. I went also to the Marine hospital and saw four of the crew of the barque sick with the coast fever. They are recovering. I questioned one and ellicited the information that they left New York in December with a cargo of calicoes and various other cotton goods. They made a good passage & disposed of their cargo in the Congo River. While they were in the river they saw a Dutch man of War who did not offer to interfere with them. They flew American colors the whole time. An American took her out and was to have brought her back to Cuba, but a Spaniard, who went out passenger, took the command out of his hands. Before these men left they bargained to receive eight hundred dollars for the trip.

p.8

They said, when they where in the river there were many vessels awaiting cargoes. It was their intention to have brought 1,000 negroes but they where afraid to remain, for fear of capture.

p.9

The board of Engineers who examined the engine report that it is not possible to repair the busted sylinder so as to make it durable and effective. Our chief Engineer has a plan of his own that he intends trying and if it awnsers we will continue the cruise, which the Capt is anxious to do just at this particular time. But under any circumstances we cannot remain longer on this station than two months. When we return it has been desided, I believe, to go to New York. To day I received a letter from you dated October 25th, and directed to Havana. Its journeyings, I imagine, have been almost as erratic as my own. I found it very interesting. The death of poor old “Luther Flaide” was announced. Gradually the old familiar faces which meet one at every turn of the corner, about the bar rooms &c, are fading away. They are seeking one by the repose and obscurity of the tomb. We look around and with that peculiar regretful feeling with which we contemplate the change & decay of old objects that have become endeared by association and ask ourselves whose turn next arrives? The old fellow, tho fond of his whiskey was by no means a bad man. He was one of those necessary appendages to society, tho not absolutely useful, that are indispensable.

[End of document][10]

[1] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Crusader_(1858) for more information on the ship.

[2] May Humphreys Stacey was a 21-year-old native of Chester, Pennsylvania and the son of Sarah VanDycke Stacey and Davis B. Stacey. Before enlisting in the Navy, M.H. Stacey had served in the Army, in the western U.S. territories, where in 1857-58 he was part of the U.S. Camel Corps. His journal documenting the unusual experience was later published: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015036897935&seq=9. After the outbreak of the Civil War, May H. Stacey rejoined the Army; he died in service in 1882.

[3] USS Mohawk was a 464-ton sailing screw-steamer under the command of Lt. Tunis A.M. Craven. Stacey has garbled the captured slave ship’s name – it was really Wildfire.

[4] By law, the capturing crew was awarded $25 for every African they liberated. With 507 people from Wildfire delivered to the U.S. Marshal, the total to be divided amongst Mohawk’s men was $12,675.

[5] French for “out of combat.”

[6] Crusader was under the command of Lt. John Newland Maffitt.

[7] In 1860, Key West had a population of 2,913. The 122-man crew of Crusader would have been a noticeable intrusion into the community’s regular social order.

[8] A fenced-in, three-acre compound, containing barracks, a hospital, and a kitchen, was built for the Africans at the southwestern point of Key West, near Fort Taylor.

[9] Tooth sharpening was (and is) performed amongst some West African peoples for spiritual and/or aesthetic purposes.

[10] Though the letter is incomplete and unsigned, another letter in the FKHC collection, also composed on Crusader at Key West and written in the same hand, is addressed to “Davis B. Stacey, Esqr., Father” and signed “M.H.S.”

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.