Island Chronicles, vol. 8: Jubilee – the 1863 Celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation at Key West

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

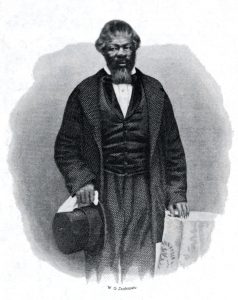

Sandy Cornish portrait by W.G. Jackman from “After the War” by Whitelaw Reid, 1866.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

Key West’s slavery and emancipation story is quite different from those of other parts of Florida or the U.S. From the first American settlement in 1822, slavery was a part of Florida Keys culture, and by 1860, of 2,913 people at Key West, 451 of them were enslaved.[1] But, as the islands were too small to support large-scale agriculture, the Florida Keys never developed a plantation economy. Instead, the enslaved were often forced to work as domestic servants or as workers in the salt manufacturing business. But surprisingly, the largest single employer of slave labor in the Keys was the U.S. government, which utilized forced labor in the construction of Fort Taylor on Key West and Fort Jefferson at the Dry Tortugas.[2] For many years, Key West slaveowners rented their people to the Army Corps of Engineers to help build the large masonry structures.

Even though construction was continuing at the outbreak of the Civil War, the forts were substantial and functional, and their presence allowed U.S. forces to keep the Florida Keys under Union control. In January of 1861, shortly after Florida seceded from the United States, Army Captain James Brannan of the 1st US Artillery at Key West, quietly marched his troops into Fort Taylor in the dead of night, while the town slept. With Army troops then manning the fort and its cannons, and Navy ships guarding the harbor, the U.S. military commanded the city. Shortly after, Fort Jefferson was firmly under Union control, too. The secessionists had been outwitted and the Confederacy never gained a foothold in the Florida Keys.

Slavery, though, continued on the islands, but having federal troops in charge did begin to weaken it. By the fall of 1862, social, legal, and military attitudes toward the “peculiar institution” began to openly change. On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln issued his “Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation,” which announced that enslaved persons in states engaged in armed rebellion against the U.S. who escaped to behind Union lines would be freed, and that all slaves would be freed on January 1 of the new year.[3] But even before Lincoln issued his order, “skedaddling,” or running away to freedom, had already become an option for many enslaved islanders. The New Era newspaper of Key West reported on the issue and noted an emboldened, shifting attitude amongst the island’s Blacks, who were secretly gathering to envision a future without slavery: “…a mass meeting was held at the Salt Ponds, and after a few most eloquent addresses by the shining lights of these descendants of Ham, a declaration of Independence was read…,” the account reported.[4]

At much the same time, island resident and slaveowner Christian Boye wrote, “The abolitionists are determined at any hazard to let the slaves free, without compensation for his loss…”[5] And after grumbling about Blacks gaining, in his view, disproportionate rights, Boye also lamented that “Col Morgan commanding here[6]…has issued a proclamation declaring all slaves free…We share all alike, all my slaves have run away.” But no one was really freed, at least in any legal sense. Key West’s New Era newspaper clarified that Morgan, in line with Lincoln’s edict, had “…simply offered an asylum and protection to slaves who might escape to our lines, and take service as nurses in the hospital and laborers for the Quartermaster’s Department.”[7]

Whatever the nuances, the combination of a strong Union presence (punctuated by Col. Morgan’s approach), and Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation, had a big impact on the nature of slavery at Key West. On October 17, 1862, a correspondent for the New York Times wrote a description of how the situation was changing: “Here [the slave] quietly leaves his old master or mistress, and seeks and obtains other employment, or perhaps builds himself a house from his previous savings, and may be seen at his daily toil as if no important event to him or his has happened. It should be understood that all slaves here are practically free. They are not returned to their owners, nor in the least restrained by any authority from employing themselves as best suits them and retaining their wages. The master is not allowed to inflict any punishment. This condition of affairs, thus far, has produced no disturbance or difficulty, beyond the mere fact that some owners have forbidden employers of their slaves to pay their wages to them, and whenever the servants find it withheld, they at once seek other employment where the wages are sure for their own pocket. Col. Morgan, who is in command here, has merely pursued a passive policy of non-interference, except to restrain all personal violence as between master and slave.”[8] Certainly, even if the new rules did not offer full emancipation (the enslaved were still owned and denied many basic rights) the situation in Key West was shifting, and the power of slavery over its victims was weakening.

On January 1, 1863, when President Lincoln issued the full Emancipation Proclamation, the edict was valid and enforceable at Key West and the Dry Tortugas, which were governed by U.S. law and not exempted from its effects.[9] That news was distressing to Key West slave owners, some of whom had invested in humans solely for the purpose of renting them to the government. James Filor, one of Key West’s largest slaveowners, wrote President Lincoln to encourage him to exempt Monroe County from emancipation, noting that he and other residents had sworn their loyalty to the United States and had even been encouraged by government engineers to capitalize in slaves. “I take the liberty of addressing you on the subject — having been a resident of Key West for the past 28 years and largely interested in slave property there, & which interest has been at various times increased at the assurance of Army officers of constant employment on the Public Works [i.e., the forts] …,” Filor wrote to the President.[10] But Lincoln was not swayed.

News of Emancipation Finally Reaches The Island

It took some time for official word of the proclamation to travel from Washington to the remote island community, but on January 18, 1863, the news arrived at Key West. “By the mail this morning the Emancipation Proclamation of the President has been received, whereby all the slaves in Florida have been declared free. Key West is no exception…,” wrote an island correspondent.[11] Another eyewitness wrote, “The proclamation arrived by yesterday’s mail…the colored people of all ages wear cheerful countenances, with a manner and demeanor that plainly indicates both gratitude and appreciation.”[12] But not everyone at Key West was cheered by the news, as the upheaval of a long-standing social order was worrying. When news of the proclamation arrived, one resentful islander wrote, “The colored ‘gemmen’ of Key West and elsewhere must not suppose that because they are free, we, the whites, are slaves, for if they try that on, as I think they will, woe betide them.”[13] The island’s newly-liberated residents had no such aspirations, but they did celebrate. Pennsylvania soldier Henry Hornbeck noted they proudly hoisted U.S. flags, and, while attending services at the local Black church, he learned the congregants intended to hold a parade for the occasion: “Thursday [January 29] was the day appointed,” he wrote.[14]

Word of Lincoln’s proclamation also reached Fort Jefferson, 65 miles west of Key West in the Dry Tortugas, if only gradually. “We received a paper on the 10th of January…containing rumors of the emancipation, which was to take place on the first, but we had to wait for another mail for the official announcement,” wrote Emily Holder, a Dry Tortugas resident.[15] When she asked an enslaved resident how he felt about the rumor, he replied, “Mighty excited, Missus. We done slept very little last night.” He also noted that if the news was true, he and a friend intended to go to one of the English islands, where slavery had long been abolished, to be “real free.” Ultimately, Holder said, “The former slaves behaved very well when the news was fully established, and as they could not get away, continued to work for themselves on the fort, as they could earn more that way than any other.”

On Thursday, January 29, as they had planned, Key West’s Black community celebrated emancipation with a parade and a dinner. Two hundred and fifty men marched through the island’s streets in two columns, flanked on either side by women and children, everyone dressed in their best clothes for the occasion.[16] The procession was headed by Sandy Cornish, the island’s most successful farmer and the de facto leader of the island’s Black community. Cornish, dressed in a black suit with sash and saber, limped as he strode because, years earlier, he had maimed himself in a bid to make himself useless as a slave.[17] “There were a few stones thrown at them in passing through Conktown,” wrote Henry Hornbeck, but the marchers were undaunted and stopped to cheer at Union Headquarters and friendly residences.[18] The parade ended at the Baptist Church, where a religious service was held. After that, at three o’clock in the afternoon, everyone made their way to the “barracoons,” a compound on the southwestern point of the island that had been built in 1860 to accommodate African refugees rescued from slave ships.[19] There, the newly freed Key Westers were joined by US military officers and supportive members of the community. Celebratory speeches and toasts were given, food was served, and the party carried into the night.

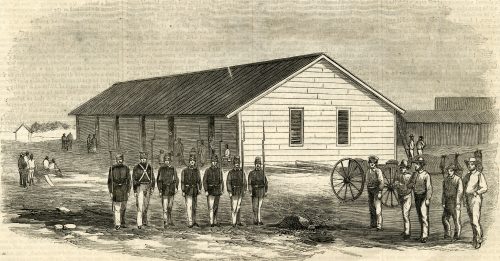

In addition to setting the enslaved free, the Emancipation Proclamation had another direct result at Key West. A secondary clause of the document mandated that “such [emancipated] persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” On February 3, 1863, just days after the celebrations on the island had ended, Col. James Montgomery arrived in Key West to begin recruiting men for the new 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Regiment of the US Colored Troops.[20] Montgomery’s enlistment drive was successful, and the U.S. Army soon had 126 new recruits.[21]

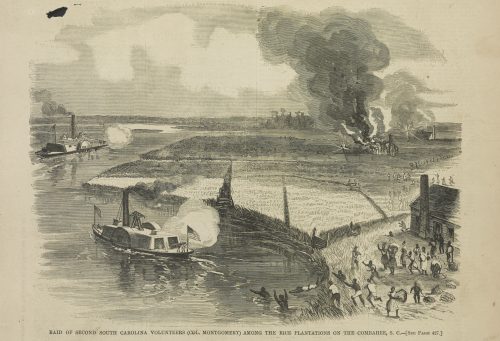

The men of the 2nd South Carolina left Key West and went to Hilton Head to begin their service. From there, the new regiment, aided by the renowned abolitionist Harriet Tubman, would soon see action in a raid on Combahee Ferry.[22] In the attack, which destroyed cotton crops and several South Carolina plantations, nearly 750 enslaved people were liberated from Confederate control. The effects of emancipation at Key West had quickly multiplied: President Lincoln’s proclamation freed previously enslaved islanders immediately and forever, which allowed many of them to join the Union cause, and, within weeks, liberate hundreds of other people – actions that helped to shape the outcome of the Civil War.

Transcribed Newspaper Accounts of the Emancipation Day Parade at Key West, Florida

[1] Browne, Jefferson B. (1912). Key West: the Old and the New, The Record Company, St. Augustine, p.173.

[2] Smith, Mark A. (2008). Engineering Slavery: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Slavery at Key West, Florida Historical Quarterly, 86(4):498-526.

[3]See: www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals_iv/sections/preliminary_emancipation_proclamation.html

[4] “Local Matters. Skedaddled.” The New Era, September 20, 1862. p.1.

[5] Boye, Christian (1863). Letter to his son dated September 23. In Schmidt, Lewis G. (1992). The Civil War in Florida: Florida Keys and Fevers, Self-Published, Allentown, PA, p.324.

[6] Jospeh S. Morgan of the 90th New York Infantry Regiment.

[7] The New Era of October 18, 1862, as quoted in “The Herald’s Echo in Key West,” New York Tribune, November 1, 1862 p.2.

[8] “Our Key West Correspondence,” New York Times November 2, 1862, p.1.

[9] See: www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/emancipation-proclamation

[10] James Filor to Abraham Lincoln, January 03, 1863. See: www.loc.gov/resource/mal.2093400/

[11] “Interesting from Key West.” New York Herald, January 27, 1863, p.1.

[12] “Our Army Correspondence. Letter from Key West, Fla., Jan.20, 1863.” Boston Morning Journal, January 29, 1863 p.2.

[13] “Interesting from Key West,” New York Herald, January 27, 1863, p.1.

[14] Pahre, Anne L.H., editor (1990). The Civil War Diary of Henry Hornbeck. Unpublished, Ms. Copy on file at Florida Keys History Center.

[15] Holder, Emily (1992). “At the Dry Tortugas During the War,” The Californian Illustrated Magazine, Vol.2, p.103.

[16] “Interesting from Key West,” New York Herald, February 11, 1863, p.8.

[17] For a biography of Sandy Cornish, see keywestmaritime.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/v04-3_1994-spring.pdf

[18] Pahre, Anne L.H., editor (1990). The Civil War Diary of Henry Hornbeck. Unpublished, Ms. Copy on file at Florida Keys History Center.

[19] See www.melfisher.org/copy-of-african-cemetery-1860

[20] The New Era, February 14, 1863, p.3. Montgomery was a staunch Kansas abolitionist who advocated for guerrilla style warfare to combat the forces of slavery and the Confederacy.

[21] See https://keywestmaritime.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/v23-4_2013summer.pdf

[22] See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raid_on_Combahee_Ferry

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Want to catch up on other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.