Island Chronicles, vol. 15 – Lifting a Locomotive: The Remarkable Salvage of the Brig Cimbrus, 1853

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

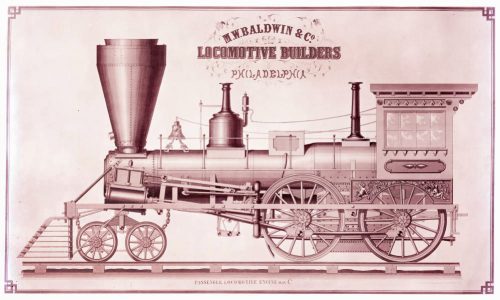

1850s Passenger Locomotive Engine, Plan C, M. W. Baldwin & Co. Locomotive Builders, Philadelphia. The locomotive salvaged by Key West wreckers in 1853 would have been much like this model. Image: DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

By the sheer nature of salvaging wrecked ships that carried any manner of goods, the wreckers of the Florida Keys regularly encountered strange, unpredictable situations that tested their knowledge and their talent. Every vessel that wrecked on the reef was unique, and quick thinking and solid maritime skills were required for each. Surely, though, one of the most challenging situations in the history of Florida Keys wrecking happened in 1853, when a group of Key West wreckers was confronted with having to recover a sunken steam locomotive.

On February 21, 1853, the 92-foot-long, 200-ton brig Cimbrus left Philadelphia, bound for New Orleans with a general cargo that included dry goods and medicines. Its biggest freight, though, was 130 tons of iron railroad rails carried deep in the hold and an 18-ton steam locomotive mounted forward on the weather deck. The rails were shipped by the Evansville & Terre Haute line, and the train engine was being shipped by locomotive builders M.W. Baldwin & Co. of Philadelphia, all for delivery to the startup New Orleans, Opelousas, and Great Western Railroad (NOO&GW). The engine was to be the new rail line’s first, and it was dubbed “Opelousas.”

The voyage of the Cimbrus was uneventful until it reached the Florida Reef, where it was struck by bad weather. On the night of March 16, ten miles southwest of Key West, Cimbrus ran onto a reef known as the Western Dry Rocks. Captain Rufus Lodge set out an anchor and managed to pull the brig’s bow off the reef, but as it swung around, heavy seas caused the vessel to strike the rocks again. Cimbrus was bilged, and it sank in 28 feet of water. The entire deck was submerged, with the forward part 6 or 7 feet underwater. Only the top of the brig’s house stood above the waves, and the crew clambered there for safety.

A Wreck Among The Breakers. From “Along the Florida Reef” by Charles Holder, Harpers New Monthly Magazine, Vol.XLII, 1871. Monroe County Public Library/Florida Keys History Center Collection.

At daylight on March 17, Key West wrecker John P. Smith of the schooner Dart saw Cimbrus’ dilemma. He approached the wrecked ship and offered his assistance to Captain Lodge – an offer that was accepted. The crew was promptly taken off Cimbrus and transferred to the Dart. Eight other wrecking vessels soon joined Dart to assist in recovering items from the stricken brig, but the bad weather hampered their success. That night, most of the wreckers returned to Key West to find safe harbor.

The next morning, despite high winds and seas, the wreckers returned to Cimbrus and managed to get alongside the wreck and save a few more items. At noon, though, the surging water burst open the main hatchway, and cargo began to wash out. The wreckers followed the drifting bundles and grabbed what they could. For another week, the bad weather continued. All the wreckers could do was station themselves inside the reef and intercept cargo that floated out of Cimbrus and was carried toward them by the wind and the waves.

The weather finally abated, and salvage divers were able to enter the Cimbrus’ hold and retrieve (formerly) dry goods, crockery, hardware, and iron rails. By an agreement made between Capt. Lodge, Admiralty Court Judge William Marvin, and the U.S. Marshal, the salvaged goods were sold as soon as they arrived at the dock. Unfortunately, much of what was recovered was so badly damaged by the water, it was nearly worthless.

The diving lasted only two days before another gale passed through the area and broke Cimbrus to pieces. The heavy locomotive on deck held down the forward part of the hold and pinned some of the cargo inside, but, otherwise, Cimbrus came apart. Most of the cargo was tossed and scattered across a shallower part of the reef, in 12 to 18 feet of water. At this point, about half of the wrecking vessels pulled out of the recovery effort. Those that stayed had to adjust their recovery strategies.

The Wrecker. From “Wrecking on the Florida Keys” by Charles Nordhoff, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol.XVIII, 1859. Monroe County Public Library/Florida Keys History Center Collection; gift of Corey Malcom.

Retrieving iron from the sea floor

Because the wreck was on the outside of the reef and adjacent to deep water and the Gulf Stream current, calm weather was required for any continued success. Once conditions moderated, divers once again began to retrieve items from the sea floor, mostly iron rails and smaller parts of the locomotive. The wreckers also began bringing up an even larger part of the rails with a set of iron tongs they had fitted with long wooden handles. By April 6, they had recovered 75 tons of iron, and a mere two days later the total had reached 130 tons.

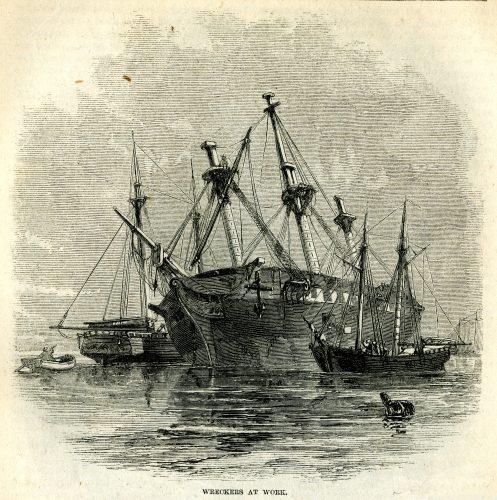

The wrecking team also began to strategize about how to raise the locomotive, which was 12 feet underwater, and they soon devised a plan to raise it using a large hulk. On April 8, they rented an old brig and began to fit it out for lifting. They rigged the brig with “sheers,” or shear legs – A-frame style lifting devices made of long, upright timbers that splayed at the bottom and came together at the top, where they were fitted with “heavy blocks and falls.” The team had to wait another two weeks for a break in the weather, but on April 27, they had their chance to recover the train engine.

As lead wrecker John P. Smith explained: “by watching an opportunity the brig was got over the engine…” Divers had run cables to and under the locomotive, which were attached to the lifting blocks. “With great labor and much time,” the crew skillfully used the tackle, and, with plenty of heaving and pulling, the Opelousas was hauled up. It is not clear if the engine was simply lifted toward the belly of the brig until it was fully clear of the bottom and lashed in place underwater, or if it was actually hauled on board. In either case, the hulk and its prize were towed to Key West. Once the brig was docked, the engine was lifted onto the wharf with more “great labor.”

Wreckers at Work. From “Wrecking on the Florida Keys” by Charles Nordhoff, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol.XVIII, 1859. Monroe County Public Library/Florida Keys History Center Collection; gift of Corey Malcom.

The cleaning and reassembly of the salvaged locomotive and its components began straight away. At much the same time, an agent for the railroad came to Key West, and he was prepared to repurchase the locomotive, but he was also scheduled to sail for Havana and needed an appraisal of the engine quickly. On April 30, attorneys for wrecker John P. Smith sent a notice to Judge William Marvin that an immediate evaluation was necessary. Marvin agreed, ordered it done, and the appraisal was returned on May 2. The restoration of the engine continued, and a May 8 report said, “The locomotive intended for the Opelousas Railroad, which…was raised from the wreck of the brig Cymbrus [sic] and taken to Key West, has been overhauled and put together, all parts being perfect. Steam was got on a few days ago, and the wheels set in motion. It worked perfectly, and it only needed a track to show its full power.” Success!

On May 23, over two months after the Cimbrus had wrecked on the reef, Judge Marvin issued his ruling on the case: “The value of all the property saved is $18,264.19 – I shall decree one half of the net value of the property saved as a reasonable salvage,” he declared. Though a fifty percent award would have normally been considered good, in this case most of the recovered goods were so damaged they had brought little money. Minus the cost of wharfage, storage, labor, and other expenses, the wreckers saw little reward for their efforts. The Key West correspondent for the New York Herald noted their misfortune, “This will give the wreckers about $5, on an average, apiece, for six weeks work.” Even the locomotive they worked so determinedly to recover had fetched a poor return: “The engine was bought by the underwriters for $3,200 – some $1,300 less than the appraised value,” wrote the Herald.

The dealings at Key West had reached their end; it was time for all to move on. On June 2, with his brig Cimbrus lying in eternal ruin at Western Dry Rocks, Capt. Rufus Lodge boarded the steamer James L. Day and left Key West for New Orleans. A little over two weeks later, another ship arrived to transport the iron rails recovered from the wreck. And on July 8, the schooner Patrick Henry arrived to at last deliver the locomotive to the NOO&GW Railroad. It arrived safely in New Orleans on July 21. At the same time, consignees of cargo carried on the Cimbrus were advised to turn in their paperwork to insurance adjusters and settle their claims.

After the Opelousas arrived in Louisiana, NOO&GW Superintendent B.H. Payne suspected that the engine was used and not new, and that the Baldwin Company had committed fraud. No formal complaint was ever filed, though, and it is not clear if the “used” aspects he observed were simply water damage. Whatever the case, any doubts the company had about the locomotive were quickly put to rest; the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported on August 6, “They received it about a week or so ago from the Key, and no doubt it will soon be put to work on that portion of the [rail]road completed from Algiers to some distance above Gretna.” The convoluted journey of the locomotive Opelousas – including a month-long stint undersea at a remote Florida reef; resolved only through the dedicated and skillful work of Key West wreckers – had reached its end. It was time to ride the rails.

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.