Island Chronicles, vol. 10: ‘Time is not enough for me, I need eternity’ – The brief, brilliant life of Juana Borrero Pierra

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

“Time is not enough for me, I need eternity”: The brief, brilliant life of Juana Borrero Pierra

Over the last two centuries, Key West has been a place of refuge, liberation, and opportunity for countless thousands Cuban exiles. In the nineteenth century, many people came to the island city to escape war and conflict that came with Cuba’s independence movement. In more recent times, Cubans have escaped the political persecution and economic strife that followed the 1959 communist takeover of the island. These displaced immigrants brought with them a multitude of talents and skills, but perhaps one of the most gifted exiles was a young woman named Juana Borrero Pierra. Her story is that of a precociously gifted poet and painter, but it is also a potent reminder of the deep and strong connections between Key West and Cuba – ties that forever bind the islands’ cultures.

Juana Borrero was born on May 17, 1877, in the western Havana neighborhood of Puentes Grandes, and she was the oldest of seven siblings. Her middle-class family was talented and educated; her father, Esteban Borrero y Echeverria, was a physician and a poet. He was also an anti-Spanish patriot and a veteran of the “Ten Years’ War” (1868-1878), the first of Cuba’s liberation wars. Juana’s mother, Consuelo Pierra y Agüero, was also an accomplished poet, as would be her sister, Dulce Maria, too. The family’s large home was a hub for Havana’s intellectual, artistic and liberal political circles.

At a young age, Juana began to show an aptitude for arts and language beyond her years: She wrote her first poem at age four, and her earliest known drawing – a skillful depiction of a carnation and a rose she titled “Romeo y Julieta” – was made when she was five. Her first published poem appeared in the leading Cuban periodical La Habana Elegante when she was thirteen.[1] As was customary for girls of that place and time, though, Juana did not attend school; her only taste of formal education came at nine years old, when, for a few months, she attended Havana’s San Alejandro Academy. Instead, her parents took responsibility for her instruction, and they drew on their connections from the arts community and found mentors to help Juana hone her innate talents.

Juana first took painting lessons with artist Dolores Desvernine, who introduced her to techniques and methods that would help her to better express her natural abilities. But perhaps most notable of Juana’s teachers was the renowned Cuban painter Armando Menocal, who remembered Juana telling him, “Do not explain theories to me, as I find them useless. Paint a little on the canvas, and that way I will understand.”[2] As Juana’s talents became increasingly apparent and her art ever more sophisticated, Menocal began to present her works at Havana’s Salon Pola gallery, and he eventually organized a solo exhibition for her. With the fundamentals given to her by these mentors, Juana began to fly on her own.

In July of 1892, on the pretense of his daughter needing additional painting lessons, Esteban Borrero took Juana to New York City.[3] (He was instead attending a meeting in support of a Cuban insurrection.) Juana was amazed by the city, but more significantly she and her father met with the great Cuban revolutionary leader José Martí. In a gathering at Chickering Hall, she read a patriotic poem she had written, her father spoke, and Marti recognized them both. The two Borreros also presented some of Juana’s paintings to Martí.[4]

Back in Havana, Esteban introduced his daughter to the young Cuban poet Julian del Casal. Casal was impressed by Juana and her creativity, and they soon formed a close, nearly romantic connection. Both were attracted to subjects of love and tragedy, and they inspired each other. In the title of a poem he dedicated to her, Casal gave Juana a moniker by which she is often remembered – La virgen triste (The sad virgin).[5] Casal died suddenly in late 1893, not long after the two had had an unexplained falling out. Because she had not reconciled with her dear friend, Juana was devastated, and Casal’s death sent her mind – and her art – into a place of sadness, mortal anxiety, and beauty. Lines from her poem Vorrei morire typify the mix of her feelings: “Quiero morir cuando al nacer la aurora / su clara lumbre sobre el mundo vierte / cuando por vez postrera me despierte / la caricia del Sol, abrasadora. (I want to die at the coming of the dawn / as its clear light pours over the world / as I wake up for the last time / to the caress of the sun, burning.)

Juana’s grief was mediated when she met the 23-year-old poet Carlos Pío Uhrbach, who had also been a friend of Julian del Casal. In late 1894, Carlos and his brother published a volume of poetry that was dedicated to their late colleague. Carlos sent an autographed copy to Juana, and she saw that it contained a sonnet dedicated to her. Juana was intrigued by the act; she reached out to him, and they began a lengthy correspondence. At last, in March of 1895, they met in person, and both fell in love. Soon they would be engaged, though secretly, because Esteban Borrero thought his daughter was too young and did not approve of the relationship. That same year, Juana’s status as one of Cuba’s leading poets was cemented with the publication of two important volumes. The first was an anthology of works called Grupo de familia: poesías de los Borrero (Family Group: Poems of the Borreros), a compilation of works written by the expanded Borrero family. And later, a stand-alone collection of Juana’s works, simply titled Rimas (Rhymes), was issued.[6]

Exile in Key West

As the Cuban independence movement turned into war in 1895, Cuban society was upended and those who supported independence were persecuted by Spanish officials and loyalists, the Borreros included. By December, the violence was coming ever closer to Havana, and Spanish volunteers took over the Puentes Grandes neighborhood. Esteban Borrero knew that, because of his revolutionary politics, his family was at risk and that he would likely be jailed or even executed. It was time to go. The family made plans to escape to Key West, and on January 18, 1896, the Borrero family boarded the steamship Olivette for the small island city 100 miles to the north, to find refuge with the many other Cuban exiles already there.[7]

Esteban Borrero had heard that the Duval Hotel was run by a man supportive of Cuba’s freedom, and he found a room for his family there. Immediately after their arrival to Key West, Juana composed a verse that laid bare the torment she felt on leaving her homeland. It is a work that has continued to serve as the cry of Cuban exiles well into the modern era:

Los Proscriptos (The Exiles)

“When the distant shadows evanesced within the horizon, the beloved homeland disappeared behind the horizon. Night advanced over the calm sea and its darkness also reached the human souls while its cold fog lent sadness to those absent from their country. From the roundhouse and under the infinite sky full of quivering stars, I stood staring at that line where sea and sky meet. Nostalgia filled my heart while tears filled my eyes, as I thought of my beloved land which remained behind me in the shadows. To bid farewell to one’s home, to one’s dearest loved ones, to the suffering homeland, is certainly very sad. The intimate rupture within our heart hurts more because we cannot forgive ourselves for this unwilled expatriation; we feel ungrateful abandoning the distressed country.

Facing us is the unknown, a strange land, a shadow, the sad night of the proscribed nostalgia. Behind us is the land we adore, where we learned to worship an ideal of glorious redemption, and where we leave friends who love us and brothers who fight for liberty.

The uncertainty of an unfortunate future and the desolate realization that the past must be definitely buried cause the exile’s soul to succumb as it is tormented by sorrows and dreams that like the stars no longer give light.

Between two infinite sorrows, between the abysses of darkness, between two dark horizons, one travels ominously to the unknown and strange region. One must leave behind ideals, sweet dreams now dead, aspirations to happiness. The horizon in front of us brings tears and our souls receive the frost of an annihilating nostalgia. (Key West, 1896).”[8]

After a week in the hotel, Esteban managed to secure an apartment above Day, Allen & Co., a furniture store in the 300 block of Simonton Street. Juana, feeling sullen and homesick, called their new abode a “Bohemian burrow,” and described to Carlos Pío, “I am in a kind of spacious and cold attic, whose oblique roof seems to oppress and suffocate me… From here, I see the stars trembling like tears.”[9]

Juana desperately hoped that Carlos Pío would find his way to Key West, and she wrote him many letters about their reconnecting. She was also feeling ill and was plagued by pain in her back, which gave her an ominous feeling about her future. She wrote to Carlos, “You can barely see two blocks [from the apartment]. Not a long distance. The trees pitch in the night like pensive and gloomy spirits. Sometimes in the evenings I go for a walk over the graves. Here, perhaps, I will sleep too.”[10] Though Juana did not feel well, she made friends in Key West (she grew particularly close to a young nun at the Convent of Mary Immaculate), and her family threw themselves into supporting the Cuban independence movement. Her father gave speeches at the San Carlos Institute to help raise funds for the patriot fighters, and the Borrero women sewed clothes for them.

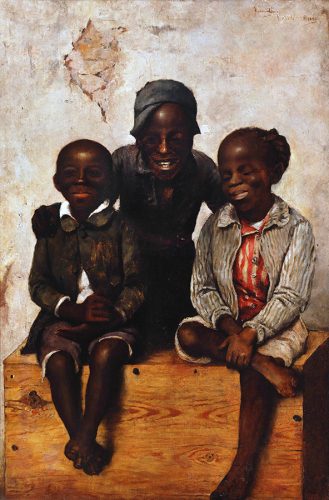

Juana also spent considerable time painting while at Key West. It is said that she painted a Madonna for the church, but sadly the whereabouts of most of her Key West artworks is not known – the paintings were likely sold, given to friends, or simply lost to time. Fortunately, one of her Key West paintings, Pilluelos (Urchins), has survived and it is considered her masterwork. The sophisticated, realistic depiction of three Key West children is one of the few from the time to depict people of African descent as the primary subject.[11] Pilluelos hangs today in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Cuba, where it is described as “one of the most notable pieces made during the 19th century.”[12]

Juana’s busyness masked her increasingly poor health, though. By the middle of February, she was diagnosed with typhoid fever and was no longer able to function normally. She sent many pleas to Carlos to visit her, but he was unable to cross to Key West from Cuba. Her last letter to him was on March 3, and she wrote, “How sadly I must tell you that I am not well! What I have is typhoid that has become critical. Convalescence will be rapid. But how my soul suffers! Horrific medicines, quinine injections, caustics, icy baths, and countless exasperating indignities that I have to accept in order to be cured.”[13] It became apparent, though, that Juana would not be cured, and she knew it. Days later, as disease consumed her and she lay dying and too weak to write, Juana dictated one of her finest poems to her sister. It was called Ultima Rima (Last Rhyme), and she dedicated it to her beloved Carlos:

Última rima

Yo he soñado en mis lúgubres noches,

en mis noches tristes de penas y lágrimas

con un beso de amor imposible,

sin sed y sin fuego, sin fiebre y sin ansias.

Yo no quiero el deleite que enerva,

el deleite jadeante que abrasa,

y me causan hastío infinito

los labios sensuales que besan y manchan.

¡Oh, mi amado! ¡mi amado imposible!,

mi novio soñado de dulce mirada,

cuando tú con tus labios me beses

bésame sin fuego, sin fiebre y sin ansias.

Dame el beso soñado en mis noches,

en mis noches tristes de penas y lágrimas,

que me deje una estrella en los labios

y un tenue perfume de nardo en el alma!

Last Rhyme

I have dreamed in my gloomy nights,

in my sad nights of sorrows and tears

with a kiss of impossible love,

without thirst and without fire, without fever and without desire.

I do not want the delight that enervates,

the panting delight that burns,

and they cause me infinite boredom

the sensual lips that kiss and stain.

Oh, my beloved! My impossible beloved!,

my dream boyfriend with a sweet look,

when you kiss me with your lips

kiss me without fire, without fever and without desire.

Give me the kiss I dreamed of in my nights,

in my sad nights of sorrows and tears,

leave a star on my lips

and a faint perfume of tuberose in the soul!

Juana Borrero died on March 9, 1896; two months shy of her nineteenth birthday. Her sister remembered many years later that Juana died sitting in her bed, propped by pillows, with her parents by her side. Juana had asked for some of her hair to be cut, and for it to be given to Carlos Pío. This was done. Juana died with her eyes open, and that was how she was buried.[14]

Rediscovery

Juana was interred in the Key West Cemetery in the grave of a family friend. After the Spanish-American war, her family returned to Cuba. They found that Spanish loyalists had raided their house and destroyed the contents. Much of Juana’s artwork was gone. Fortunately, her poems had been published and were available elsewhere, her diary and many of her letters had been saved, and some of her paintings were in the hands of friends. These works have become her legacy.

Because Juana also wrote and painted from exile, her story and her art became touchstones for those who fled the 1959 communist takeover of Cuba. Her longing for home was like theirs, and Juana’s reputation amongst the new refugees grew. People began to grow curious about her. Notably, because she had been buried in someone else’s grave, her final resting place was unknown, a troubling circumstance for her admirers. A professor of Hispanic literature set out to change that.

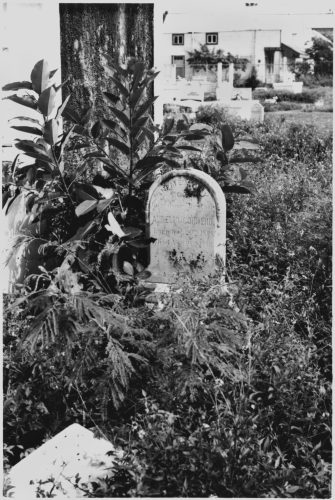

In April of 1972, exiled Cuban professor Octavio de la Suarée tracked down Juana’s sister Mercedes and interviewed her. Mercedes recollected that Juana had been buried in the grave of a young man named Aurelio Cordero, whose family had become close with the Borreros while they were in Key West. Armed with that knowledge, and after corresponding with the Key West city manager and the cemetery sexton, La Suarée organized a visit to the island by the Junta Nacional de Arqeologia y Etnologia de Cuba en Exilo, an exile group dedicated to the archaeology and history of Cuba. Their goal was to find Juana. The team located the Cordero family plot, and soon after they found Aurelio Cordero’s tombstone. On November 26, 1972, with permission from the City of Key West, they began the exhumation of the grave.[15]

Indeed, and as expected, the team uncovered a skeleton with features indicative of that of an 18-year-old woman. There was no doubt that after 76 years of being anonymously buried Juana was found! Her remains were gathered into a temporary ossuary, and after a brief memorial service, the box was placed in a niche in the mausoleum of the Cuban fraternal order Caballeros de la Luz. Just over a year later, on December 2, 1973, after funds had been raised for a new grave, Juana Borrero was reburied in her own plot. Mayor Charles “Sonny” McCoy declared the date “Juana Borrero – Glory of Cuba Day” for the City of Key West.

Today, Juana Borrero’s grave – modest and somewhat hard-to-find – holds the young, exiled woman who across her short years left a powerful and significant legacy. Hers was the rare adolescent female voice from the era of Cuban independence. And even while dying in exile in Key West she continued to create great and lasting art. Neither youth nor looming mortality could hinder her creativity. As one writer has noted, a line of Juana’s best summarizes her short but immense life: “No me basta el tiempo, necesito la eternidad (Time is not enough for me, I need eternity)”.[16] Fate has placed Juana Borrero’s eternity in Key West. It is now up to us to remember her.

[1] Garica, Maria Cristina (2006). “Borrero Pierra, Juana (1877-1896)” in Latinas in the United States, A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol.1, V.L. Ruiz & V.S. Korrol (eds.). Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

[2] Picart, Gina (2016). “Juana Borrero, poeta consagrada y pintora desconocida” at ginapicart.wordpress.com/2016/05/17/2148/

[3] Pérez, Blas Nabel (2022). “Juana Borrero: Mítica Niña Prodigo.” At www.lajiribilla.cu/juana-borrero-mitica-nina-prodigio/

[4] Nunez, Ana Rose (1975). Juana Borrero: Portrait of a Poetess, The Carrell, Journal of the Friends of the University of Miami Library, Vo.16, pp.1-24.

[5] Picart, Gina (2023). Juana Borrero, musa del movimiento modernista en Hispanoamérica. At https://ginapicart.wordpress.com/2023/05/22/juana-borrero-musa-del-movimiento-modernista-en-hispanoamerica/

[6] Juana Borrero. Obras de la Escritora: originales y editadas, at https://eladd.org/otras-autoras/juana-borrero/

[7] Cuza, Belkis Male (1984). El Clavel y la Rosa: Biografía de Juana Borrero. Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana, Madrid.

[8] Translation by Graciella Cruz Taura, in Núñez, Ana Rose (1975). Op.cit.

[9] Cuza, Belkis Male, Op.cit. p.188

[10] Cuza, Belkis Male, Op.cit. p.190

[11] Sullivan, Edward J. (2014). From San Juan to Paris and Back: Francisco Oller and Caribbean Art in the Era of Impressionism. Yale University Press, New Haven.

[12] See: https://www.bellasartes.co.cu/obra/juana-borrero-pilluelos-1896

[13] Cuza, Belkis Male, Op.cit. p.203

[14] Letter by Mercedes Borrero, dated December 14, 1972, at Havana. Copy on file at Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Library.

[15] De la Suarée, Octavio (1973). Acta de exhumación de Juana Borrero (1877-1896). Copy on file at Florida Keys History Center, Monroe County Library.

[16] Núñez, Ana Rose (1975). Op.cit.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.