Island Chronicles, vol. 11: The Disaster of the 1733 Nueva España Flota (New Spain Fleet) as Reported in English Newspapers

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

The 1733 Fleet

Spain’s colonial maritime empire is largely remembered today for its treasure-laden galleons. For centuries, these armed cargo ships were organized into convoys that carried the output of mines and plantations from the American colonies across the Atlantic Ocean to Spain. For a period of over 250 years, at least two large fleets sailed annually – one from South America (the Tierra Firme galleons), and one from Mexico, which was then known as New Spain (the Nueva España Flota). These ships would meet with other vessels in Havana and then sail to Spain as a group.

On May 25, 1733, the Nueva España Flota, under the command of Don Rodrigo de Torres, left Vera Cruz for Havana. The ships were loaded with silver, spices, porcelain, and a wide variety of other commercial cargoes, all intended for Spain. After taking on passengers and final cargoes and provisions, twenty-one ships left Havana on July 13th. Not long after, the crews sighted Key West and then adjusted their course to carry them eastward through the Florida Straits. The following evening, they began to experience a strong north wind, and experience told Torres and his captains that a hurricane was imminent. By the morning of the 15th, the winds clocked around to the south, and the fleet was driven onto the reefs and shoals of the Florida Keys. When it was all over, twenty vessels were wrecked; scattered along the Upper Florida Keys, from present-day Marathon to Elliott Key.

News of the tragedy quickly reached Havana, and salvage crews were dispatched immediately to offer relief to the victims of the disaster. They found almost all the ships hard aground and dismasted along the reefs and shoals fronting the Florida Keys. A camp was quickly established on one of the nearby islands, and it served both as a refuge for the survivors and the command center for the extensive salvage operations that followed.

Though many of the ships were badly damaged, most were in shallow enough water that it was relatively easy to recover the cargoes, and a variety of techniques were employed to rescue whatever could be recovered. According to the news accounts only one of the wrecked ships – the private merchant vessel Nuestra Señora del Rosario – was refloated and put back into service. The others were lost, and many were burned to the waterline to recover valuables in their holds and iron fittings from their hulls that were otherwise inaccessible. Ultimately, more treasure was recovered from the wrecks than had been registered when they sailed.[1]

Beginning in the 1930’s and continuing through the 1990’s, many of the wreck sites were located by US treasure hunting operations, and these groups worked to recover much of what had been lost or left behind by the Spaniards. But many of the wrecks remain, and today thirteen of the 1733 shipwreck sites are identified in the waters of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Biscayne National Park. A program called the “1733 Spanish Galleon Trail” has been developed to encourage interested divers to visit these wrecks as a hands-on way of learning about Spain’s important maritime system and the tragedy suffered by the New Spain fleet nearly 300 years ago.[2]

The English News Accounts

Articles about the disaster published in a variety of weekly English broadsheets represent the first newspaper reporting from the Florida Keys, and it is interesting to note how information traveled from the remote reefs and islands to readers across the Atlantic. From the bylines, it is evident the primary mechanism by which publishers received information was through the sharing of letters. Some were written by ships’ crews who had sailed upon the scene of the wrecked fleet and shared the news upon arrival to their destination. Word of the disaster also came from the correspondence of British officials stationed in both Spain and France. And other news of the fleet came via letters written by a variety of sources in Havana, South Carolina, Jamaica, Spain (chiefly Cadiz), France, Holland, and Italy. Whether the letters were private correspondence that was shared secondarily with the newspapers, or if they were messages sent directly to publishers is not clear. Whatever the case, the combination of an early, informal maritime postal system combined with a mushrooming English newspaper industry, allowed a tremendous amount of information concerning events at the Florida Keys to reach printing presses and be shared broadly with the world.

Because much of Spain’s colonial wealth was aboard the fleet, and the potential loss of the treasure would have had an economic impact well-beyond Spain’s borders, the disaster was big news; English papers eagerly carried the story of the fleet’s drama. Though the accounts were sometimes erratic and conflicting, when aggregated they added up to a comprehensive and timely interpretation of what had happened to ships, their crews, and the cargoes.

The news first broke in England one month after the hurricane – about as quickly as was then possible – when the scattered wrecks were first seen within two days of the disaster by the crew of an English merchantman whose captain reported the news back home. The information came so soon after the loss that announcements of the fleet’s departure from Havana were still arriving well after the news of its problems.

Giving confirmation to the rumors, other vessels sailing through the Gulf Stream passed the wrecked fleet in the days that followed, and they offered brief but vivid perspectives of the Spanish salvage of the wrecks. One account reads:

“… I saw six large Ships on Shore on the Marteires,[3] and one that was afloat; her Masts were gone, and they had got up Jury Masts, and was near fitted. The People had 30 Tents on the Shore, made with the Ships Sails. We also saw two or three Boats pass from the Shore to the Wrecks, and a Sloop that was at Anchor. We were about a Mile distant from the Hull of one of them, and saw the men at work on board her, and also Boats which seemed to be loaden, go ashore from her. The Ship which was afloat had two Teer of Ports, and I believe was a Fifty Gun Ship. The Wrecks all appear’d to be as large as that on float.”[4]

The same article further states that the hurricane came from New Providence Island in the Bahamas, where it had struck on the 14th of July, indicating the storm was traveling generally WSW when it hit the fleet. Also, and quite surprisingly, the wreckage from the fleet scattered well beyond the Keys. Flotsam (in the form of masts, pieces of hull, and a drowned cow) was found as far as twenty-seven and a half degrees north, along the Florida Coast near present-day Ft. Pierce Inlet.[5]

The salvage of the wrecked fleet was a very large task and apparently the Spaniards were not fully equipped to handle it. As a result, not all passing ships were allowed to simply go on their way. Reports reached England of vessels being pressed into service by the Spaniards to transport salvaged cargo from the Florida Keys to Havana. Two vessels reported having to make two circuits of ferrying goods between the wreck sites and Cuba, before being allowed to continue their voyages home.[6]

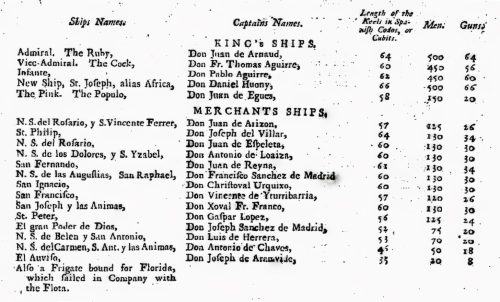

The newspapers also published detailed accounts of the storm and the sufferings of the ships and crew as they went through it.[7] And to give a sense of the scale of the loss, there is a comprehensive table outlining the names of each ship, its master, the number of guns it carried, and its size, along with the aggregate cargoes of the fleet.[8]

After a long period of waiting and wondering, four vessels dispatched to carry the salvaged treasure across the Atlantic finally arrived at Cadiz on the 19th of June 1734.[9] Included in the convoy of ships were the ships Africa and Rosario, both of which had been part of the original fleet. All that was left was the assessment of the salvage fees by the king. He did so, averaging a little over 20 per cent as a levy for the recovery, storage, and transportation of the rescued goods.[10] After safe delivery of the treasure, the news ends. From there, the business of recovering the treasure and delivering it to its intended destination was complete, and further reporting on the subject was not necessary.

The following transcripts are from articles found in the Burney Collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English newspapers housed at the British Library and available (via subscription) through an online database. The stories are presented chronologically as published and because information reached the publishers erratically, the narrative jumps back and forth at times. The original grammar and spelling have been retained, and footnotes have been added to clarify obscure terms. The antiquated writing styles used in some of the articles can be a bit challenging to the modern reader, but taken as a whole, the difficulties suffered by the 1733 fleet are presented in the texts fully and in “real time,” much as would have been experienced by readers in the eighteenth century.

English newspaper accounts of the 1733 fleet, transcribed and annotated:

[1] Smith, Roger C. (1988). “Treasure Ships of the Spanish Main,” in Ships and Shipwrecks of the Americas, George F. Bass, editor. Thames and Hudson, New York.

[2] Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research (2005). 1733 Spanish Galleon Trail: Explore the Spanish Plate Fleet Disaster of 1733. Florida Division of Historical Resources Bureau of Archaeological Research, Tallahassee. See also https://info.flheritage.com/galleon-trail/

[3] The “Marteires” (Martires, or Martyrs in English) was a colonial-era Spanish name for the Florida Keys.

[4] See entry 4: Extract of a letter from South-Carolina, July 21. St. James’s Evening Post (London) September 29, 1733.

[5] Ibid.

[6] See entry 18: London Evening Post, December 15, 1733.

[7] See entries 7 & 8: London Evening Post, October 11, 1733, and The Daily Journal (London), October 12, 1733.

[8] See entry 14: The Daily Journal (London), October 27, 1733.

[9] See entry 24: The Daily Journal (London) July 3, 1734.

[10] See entry 27: Extract of a Letter from Cadiz, dated July 27. N.S. The London Journal, August 10, 1734.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Want to catch up on the other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.