Island Chronicles, vol. 14: Stranded at Sand Key: The Banishment of the Passengers of the Steamship Philadelphia, 1852

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

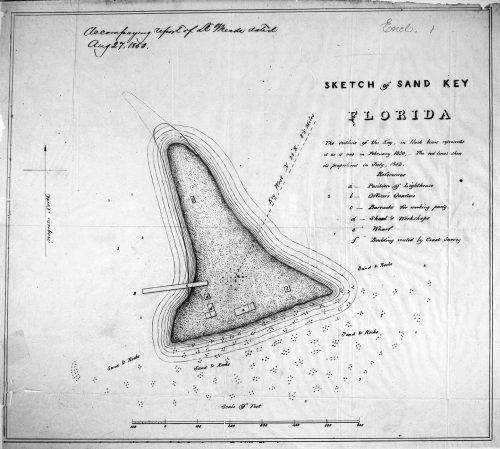

Sketch of Sand Key, Florida (from National Archives) Delineator unknown, dated Aug. 27, 1853. From Survey HABS FL-189 copy

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

In the nineteenth century, disease, particularly yellow fever, was a constant threat to the residents of the Florida Keys. Illness and infections were not well understood at the time – miasma, or foul air, was thought to be a leading vector – so residents did not always react appropriately or effectively when sickness threatened. In the summer of 1852, the steamship Philadelphia came into Key West Harbor, and the captain reported that many on board were sick with cholera. Instead of offering any substantial help, island officials turned the ship away and would not let it anchor within five miles of town. Low on coal and water and unable to proceed to another port, the captain of the Philadelphia saw that his only option was to put his passengers onto small and desolate Sand Key, some nine miles distant, and hope for the best.

Key West’s banishment of the nearly 200 needy passengers and crew on the Philadelphia was not the island’s finest moment but given the state of medical knowledge at the time, it is understandable: The Key Westers were not wholly sure of what would happen if a group of sick and dying people was allowed onshore. They did not know that cholera was spread via contaminated water or food, so their seemingly heartless response was really a matter of basic, if naïve, self-preservation.

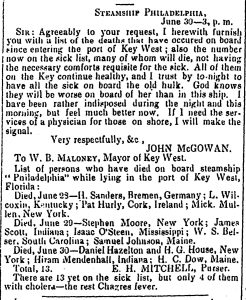

As the plight of the Philadelphia unfolded, updates were published in multiple newspapers, and those stories give an interesting framework for the events. But other, firsthand accounts by those directly involved in the affair give an even clearer picture. A copy of a diary by Philadelphia passenger James Perry Fyffe found in the Florida Keys History Center, plus letters by the Philadelphia’s Captain John McGowan, passenger Lewis Middleton, and Key West Mayor Walter C. Maloney, all published in various newspapers, offer detailed, day-by-day descriptions of events across the entirety of the steamship’s drama. These firsthand narratives were used to create the following summary. (Note: Full transcripts of these documents are appended to this post, and they are well worth reading.)

The Voyage from Panama to Key West

After the discovery of gold in California in 1849, a demand grew for travel between there and the rest of the United States. Passenger ships at the time were not able to safely traverse the southern tip of South America, and there would be no railroad across the U.S. until 1869, making the next best route to be via the isthmus of Panama. In this journey, steamships from California made their way to Panama City on the Pacific coast, from where the passengers then trekked across the relatively narrow neck of land. This overland journey was a combination of land and river travel to Aspinwall (today Colón) on Panama’s Caribbean coast. Unfortunately, the hot and wet Central American climate was the perfect breeding ground for tropical diseases, and yellow fever, malaria, cholera, and Chagres fever often afflicted those who made the crossing.

On June 10, 1852, the steamship Philadelphia, part of the privately-owned United States Mail Company’s fleet, left New Orleans for Aspinwall. It arrived safely, and on June 22 departed Panama with 225 passengers bound for Havana and then New Orleans. For a few days the voyage went well. But on June 26, things took a dark turn. Passenger James P. Fyffe wrote in his journal, “The cholera broke out today off Cape San Antonio. Its ravages have been unchecked by any medical science and it is of a malignant kind.” Within an hour of the first symptoms, ten people were down, and by midnight, twelve were dead. Sickness was in full bloom.

The Philadelphia entered the port of Havana the next morning. But as soon as it was learned that the vessel was plagued by illness, port officials became alarmed; a cannon from the Morro Castle was turned on the ship and the Philadelphia was ordered out of the harbor and given 45 minutes to put to sea. The steamship was nearly out of coal and water, and was given some, but only enough to reach Key West. So, the Philadelphia was compelled to make its way to the small island city. The crew heaved bodies overboard along the way.

On the morning of June 28, the Philadelphia, flying a yellow flag to indicate sickness on board, pulled into Key West harbor. After an examination by the port physician, the steamer was ordered to anchor in the Northwest Channel and told that water and other provisions would be sent out via lighter. Captain McGowan asked that the healthy passengers be allowed to land and that sick crewmen be placed in the Marine Hospital. That request was denied. McGowan then asked that they be allowed to use the site of Fort Taylor, then under construction and 1200 feet offshore. That request was also denied. The Philadelphia was then ordered to leave the harbor by 6 p.m. and was also prohibited from being within five miles of Key West after that time.

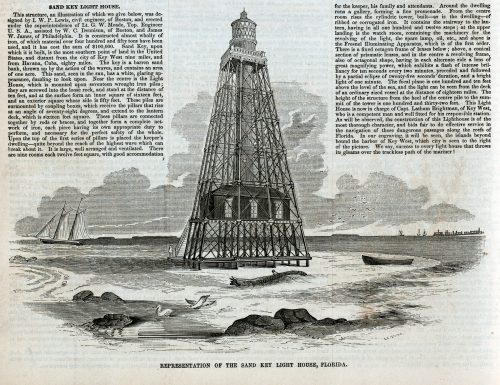

With no good options, Captain McGowan purchased a derelict hulk for use as a makeshift hospital and steered the Philadelphia toward Sand Key, a small, barren, two-acre island, located nine miles south-southwest of Key West at the edge of the Florida Reef. Construction of an iron-framed lighthouse was underway at the remote island, but the assembly crews were on summer hiatus, and the place was unoccupied. There were structures on the island: a small house for workmen, a covered dock, a shed, and two levels of the lighthouse’s iron frame. As darkness fell, Philadelphia arrived alongside Sand Key and anchored. The sick continued to die, and by midnight the toll had reached thirty.

Representation of the Sand Key Light House, Florida in 1854 by S.E. Brown. Gleason’s Pictorial, v. 7, no. 10 (1854 Sept. 9), p. 152.

At dawn on June 29th, the Philadelphia’s healthy passengers – roughly 170 people – were put ashore at Sand Key. The steamer Empire City approached, and though they wanted little contact with the stricken Philadelphia, they did take some of steamer’s mailbags. Two well-connected Philadelphia passengers managed pull strings to escape the increasingly dire situation and also got onto the Empire City. Later in the morning, the hulk was towed down from Key West. It was anchored two hundred yards behind Philadelphia, and after a shed was built on it for use as a hospital, the sick were placed on board. The hulk was a poor choice for an infirmary; it was filled with putrid bilge water and rocked badly in the seas. Conditions on the derelict were so bad that Captain McGowan complained to Key West Mayor W.C. Maloney it was like the infamous “Jersey Prison Ship” employed by the British during the American Revolution. Another six people soon died.

On Sand Key, the refugees occupied the buildings – twenty-five in the crew quarters, ten in the shed, others on the dock. Sails and tarps were draped over the emerging lighthouse structure to create a larger shelter for everyone else. Some of the castaways tried to make the best of the situation by collecting marine curiosities along the shore. Creature comforts were scarce, and shells and broken bottles had to serve as cups. As the passengers settled into their exile, the Philadelphia crew began to fumigate, scrub, and repaint the steamer.

Two days after being placed on Sand Key, trouble emerged when some people noticed their clothes and other personal articles had disappeared. A hunt for the missing goods began, and two men were soon found to be the thieves. After a makeshift trial, the two culprits were whipped for their transgressions. More excitement occurred when a squall came through and overturned a small, nearby pilot boat, throwing a man into the water. The passengers watched from shore with collective worry as he struggled, and they were relieved when he was rescued by the crew of another boat. At some other point, a few sea turtles that crawled onto the sandy shore were taken and turned into soup and steaks, giving the passengers a much-needed supplement to whatever food they had from the steamer. But, despite the occasional distractions, the time at Sand Key was mostly monotonous and hot. The Philadelphia passengers had little to do but wait for a resolution to their situation.

On July 3, five days into their stranding, “fever” appeared, and people began to shiver and shake in misery, despite the warm climate. On the bright side, though, the cholera was fading. Despite that progress, there was no indication the passengers would be allowed to leave Sand Key anytime soon. For the next few days they waited, hoping that “tomorrow” would bring their freedom. Mayor Maloney, accompanied by a doctor, visited on July 5 to assess the situation, and the two officials found that the group was in better shape than expected. With that bit of good news, twenty of the passengers managed to escape the island after they somehow found a Key West pilot boat captain who agreed to carry them to Mobile for a steep $60-per-person fare.

On July 6, the remaining castaways received word that they would be allowed to go to Key West the next day. Though it was the news they had been waiting for, many were skeptical and took it as speculation, at best. Passenger James Perry Fyffe reacted with deep cynicism, “Tomorrow, tomorrow, again, while we lie in the sand, a burning sun by day, cold chilly breeze at night. Cold chills and a burning fever. No medicine, no proper food, no comforts of any kind and that tantalizing tomorrow,”

A postcard of the Sand Key Lighthouse C 1970. Monroe County Library Collection.

The rumor was true, though, and on July 7 everyone who was well was allowed to go to Key West. After the Philadelphia’s healthy passengers were removed from Sand Key, the sick were transferred from the hulk to a building on the islet to complete their convalescence. Upon arrival to Key West, forty of the refugees immediately sailed to New Orleans on a hastily chartered sloop. Everyone else found rooms in boarding houses, and for the next few days they took in the sights of the town and island.

A group of twelve New Orleans passengers, including diarist James Perry Fyffe, booked passage on steamer Falcon. As they departed the Florida Keys on July 11, Fyffe wrote in his diary, “Farewell Key West, with your mournful memories and you, Sand Key, as we pass your low sandy shore. How much misery and suffering is connected with our short acquaintances?” (Unsurprisingly, there is no evidence he ever returned to either island.)

Two days later, on July 13, after coal had been delivered from Havana and the deep cleaning of the ship was completed, the Philadelphia left Key West for New York with its remaining passengers – minus a relatively small group of eleven still-recovering patients who were left behind under the care of the port physician. At last! After an awful two-and-a-half-week ordeal that left fifty-five people dead and saw everyone else treated as pariahs banished to a desert island by their fellow countrymen, something akin to normalcy had returned, and the journey continued.

Read 1852 letter and diary transcripts regarding the steamship Philadelphia here.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.