Island Chronicles, vol. 17 – Repeaters at Key West: Alleged Voter Fraud in the 1880 Presidential Election

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

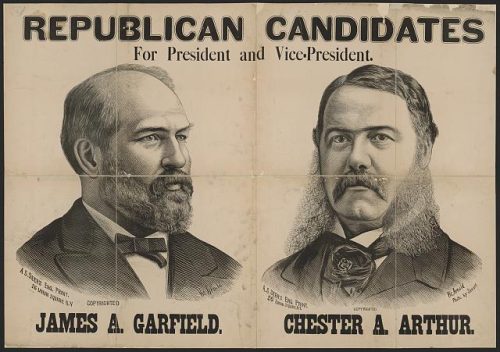

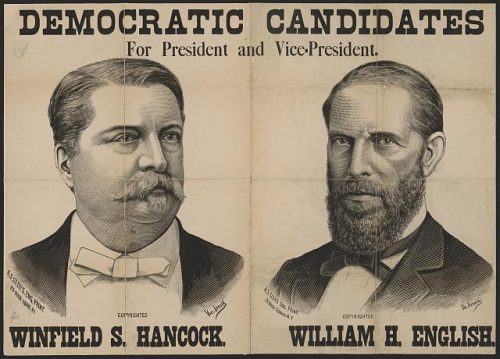

The 1880 presidential election was a contest between Republicans James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur for President and Vice-President against Democrats Winfield S. Hancock and William H. English. A variety of issues dominated the race – the appropriateness of tariffs on foreign goods, Chinese immigration, and whether U.S. monetary policy should be based on the gold standard. It was a tight battle, and both sides were looking for advantages wherever they could find them. For a weeklong period in October of 1880, Key West emerged at the center of an election fraud scandal, with supposed “repeaters”[1] being shipped to the island so they could sway the Florida vote. It was not true but that did not matter; fragments of evidence were distorted and inflated to suit political needs.

The Telegrams

In the late 1800s, before the advent of radio and the telephone, the telegraph was the primary tool for long-distance communication, and the political world relied heavily on its use. The Republican National Committee (RNC) had a contract with the Western Union Telegraph Company for communication services, and a provision in the agreement was that paper copies of all its telegrams, sent or received, would be mailed weekly to party headquarters in New York as vouchers for the bills rendered. On October 20, through the error of a Western Union employee, two telegrams sent by the RNC on October 12 were accidentally sent to Democratic headquarters.[2]

The first telegram, from RNC Chairman Marshall Jewell to Massachusetts state congressman Charles J. Noyes, read as follows:

New York, October 12th, 1880.

“Rush”

To Hon. Charles J Noyes,

Care of H. Jenkins, Jr.,

Jacksonville, Fla.

I telegraphed yesterday. I will provide, as requested, two hundred each for Callender and yourself as compensation.

MARSHALL JEWELL

The second dispatch, from Jewell to Frank Wicker, Collector of Customs at Key West and a leader of the Republican party there, read:

New York, October 12th, 1880.

“Rush.”

To F.W. Wicker

Collector, Key West, Fla.

“City of Dallas” took 150; “City of Texas,” 100; “Colorado,” 100, for Key West. Men on dock instructed to say nothing about it.

MARSHALL JEWELL

The Key West Custom House at Clinton Place, ca. 1880, with the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in the foreground. Monroe County Library Collection. This is where Collector Frank Wicker received telegrams from the Republican National Committee warning of men coming to Key West to commit voter fraud.

The clerk who received the missent telegrams forwarded them to the Chairman of the Democratic National Committee (DNC), William H. Barnum, a former U.S. Senator from Connecticut. Barnum did not return the telegrams to their rightful owner. Instead, he realized could make political hay from the cryptically worded communiques, and he promptly made copies for distribution. Barnum then gave a public address and declared that Jewell’s telegrams were direct evidence of a Republican scheme to commit voter fraud.[3]

The first telegram was clearly payment of some kind, but for what was not clear. “Barnum allowed this dispatch to go with any construction people might choose to put upon it, and it will admit of a great many when read by partisans possessed of lively imaginations,” wrote a reporter.[4] Plainly, though, the implication was that men in Florida were being paid for something sinister.

The second telegram was much more damning according to Barnum. “The numerals ‘150,’ ‘100,’ and ‘100’ in this last telegram mean so many men,” he said, adding that they were men being sent to vote illegally. “These telegrams, or rather the one addressed to F.W. Wicker, United States Collector at the port of Key West, Florida, tells its own story,” he continued, swearing that it was a “great fraud.” “The [Democratic] committee were advised, previous to the receipt of these telegrams, that the State of Florida was about to be overrun by the repeaters of our large cities. The telegrams of Mr. Jewell only confirm what the committee well know to be the fact,” he concluded.

Western Union president Norvin Green was angered by the Democrats having taken advantage of his company’s mistake. “Mr. Barnum’s act in making use of documents sent on in error and to which he had no possible claim, was a perfectly outrageous act, as it is also perfectly indefensible. It was his plain duty to have at once returned to the rightful owners that which only fell into his hands by accident,” he said. Green also demanded the telegrams not be reprinted and that any copies be destroyed. Barnum responded that the original telegrams would be returned, but that since he and the Democratic National Committee considered the contents to be political and of civic interest, they would continue to use “such copies, lithographs, etc., as they may deem best for the public good.”[5]

Some reporters were happy to run with Barnum’s allegations, and they spread the story. “Perhaps Mr. Jewell, chairman of the Republican Committee, will now explain to a curious and amused public what was the nature of the ‘150’ which he sent to Key West by the City of Dallas, the ‘100’ by the Colorado, and the other ‘100’ by the City of Texas, and why the ‘men on the dock’ were ‘to say nothing about it’? So much, we think, Mr. Jewell might grant the public curiosity,” ventured one anonymous New York writer.[6] The story grew, especially in Democratic strongholds of the South, where newspaper headlines like “Attempted Frauds Exposed. The Republicans Seeking to Steal the Vote of Florida as in 1876,”[7] and “The Tell-Tale Telegrams. A Republican Plot to Capture the Vote of Florida. Three Hundred and Fifty Men Sent from New York to Vote in the South”[8] gave added slant to the story.

Republican candidates for President and Vice-President, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur. Library of Congress.

Democratic candidates for President and Vice-President, Winfield S. Hancock, William H. English. Library of Congress.

The Truth

The Republicans denied they were sending men to Key West. Instead, they said, they were the ones trying to prevent voter fraud. And there was evidence to back their claims. RNC chairman Marshall Jewell shared his version of events and presented additional telegrams to support his case. With that, newspapers looked further into the claims, and with the added context the two telegrams leaked by the Democrats took on a more sensible tone.

Regarding the first misappropriated telegram, which mysteriously mentioned compensation, Jewell clarified that the money referred to in the note was to be sent to Massachusetts politician Charles Noyes and a Boston attorney named Callender, both of whom had gone to Florida to stump for Republican causes and were being reimbursed for expenses. The purposes of their travels were provable and not nefarious.

As for the second telegram, Jewell explained that he had received information on October 8th from the New York Collector of Customs Charles Treichel that 200 or 300 men were leaving from New York for Florida on a Mallory steamship under the sponsorship of a Democratic supporter, and it was thought the men were traveling to commit election fraud and sway the Florida vote. Based on that information, he sent the following dispatch to Key West:

New York, October 8, 1880.

To F.W. Wicker, Collector, Key West, Fla.

Mallory steamer of last week had 200 or 300 workmen for some railroad. Looks to me as if they were sent to Key West to vote.

MARSHALL JEWELL

Three days later, Jewell received another notice from Collector Treichel:

Custom House, New York, Collector’s Office,

Oct. 11, 1880,

Dear Sir: I have just received the inclosed memorandum from a perfectly trustworthy person. You remember my telling you the other night that I would try to get at the facts. Yours in haste,

Treichel

To the Hon. Marshall Jewell, Chairman of the National Committee.

This was the memorandum:

City of Dallas, 150; State of Texas, 100; Colorado, 100. Men on dock are instructed to say nothing about it. Denied in office at dock that any had gone.

That second update from Treichel prompted the October 12th telegram to Key West Collector F.W. Wicker that later fell into the hands of the Democratic National Committee. As Jewell described it, he suspected “the Democrats were exporting men to Southern Florida for some purpose; and from the history of that party, it was fair for us to assume that they were sending them there to commit election frauds.”[9] He feared the fraudsters were going to Key West and wanted the Collector of Customs there, a fellow Republican and a man he trusted, to be on the lookout for them.

The New York Herald dug deeper into the story. Reporters contacted the Mallory Steamship company and learned that hundreds of men were indeed sent to Florida on their ships, but not for the reasons the political parties had suspected or been claiming. The Savannah, Florida, & Western Railway had purchased the tickets for the men so they could help build an extension from Jacksonville to Waycross, Georgia. A representative for the railroad elaborated, “We shipped these men to push the work as rapidly as possible.” He explained further, “I can say that they were not ‘repeaters.’ Indeed, I fancy it would have taken some time to explain to them the meaning of that term, as they were immigrants just landed…The officers of this road are divided in their political views, but they have all been exceedingly annoyed at having a political construction put upon their private business.”[10]

When confronted with the fuller story and asked if he should have inquired further about the telegrams mistakenly sent to his office, William H. Barnum was unrepentant. “Who ever heard before that a criminal whose guilt was accidentally discovered should be advised of the fact before steps were taken to prevent the accomplishment of his intended crime?” he asked sharply. And after insisting that the Custom House and telegraph company were colluding with the Republicans to cover up the scheme, Barnum doubled down on his accusation: “The fact remains beyond controversy that Mr. Jewell has been caught in an attempt to carry the Florida election by fraud,” he declared.[11]

The 350 men never arrived in Key West, just as they were never supposed to. The suspicions and political ruckus over their travels came about only because both Republican and Democratic officials misread partial information in ways that reflected their fears. The Republicans were given an incomplete, back-channel story of a large group of men traveling to Florida, supposedly under Democratic control, prompting party leadership to urge their Florida contacts to watch out for fraud. (It must be said, though, that it does not appear the RNC intended to go public with their suspicions without further proof.)

The Democrats, on the other hand, took wrongly received and even more ambiguous information and quickly twisted it to suit their needs. By willfully misinterpreting cryptic telegrams and then publicly proclaiming them evidence of cheating, DNC leadership recklessly smeared their Republican opponents. And even after being confronted with a fuller story that proved him wrong, Democratic chairman Barnum stuck to his guns and continued to claim he had uncovered fraud. His goal was to keep supporters engaged, enraged, and united against the enemy. As the bigger picture emerged, though, it became clear the “scandal” was nonsense shaped only from the barest of truths. The public saw it for what it was, and the story faded from the headlines.

The 1880 presidential contest would go on to be the closest popular vote in U.S. history, with Garfield garnering only 8,355 more votes than Hancock (the electoral college went 214 to 155 for Garfield).[12] It is hard to measure the effect the tale of the repeaters at Key West had on the result, but it must have been greater than zero. Even though no men were coming to Key West, some people took the story to heart because it served their goals. Surely, the false narrative of men being shipped to vote in 1880 was not the first instance of unneeded outrage being used to influence politics, and, as we well know, it is a tactic that endures to this day. If people want to believe something bad about their rivals, they will.

[1] A repeater was a person who voted in more than once in the same election. The term “colonizers” is also used in the documents to describe the men, implying they were traveling from one place to another to affect the vote.

[2] Davenport, John I. (184). History of the Forged Morey Letter, Published by the Author, New York.

[3] Anonymous a (1880). “Campaign Curiosities,” New York Herald, October 22, p.3.

[4] Anonymous c (1880). “Those Florida Despatches.” New York Herald, October 23, p.3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Anonymous b (1880). “Republican Mules?” New York Herald, October 22, p.6.

[7] Vicksburg Daily Commercial (1880), October 23, 1880, p.1.

[8] Charleston News and Courier (1880), October 25, p.1.

[9] Anonymous d (1880). “Democratic Roorbacks,” New York Herald October 23, p.1.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Anonymous e (1880). “What Mr. Barnum Thinks About His Own Conduct,” New York Evening Post, October 26, p.3.

[12] See: www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections/1880 & www.270towin.com/1880_Election

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.

Want to receive future volumes as an email newsletter? You can sign up here.