Island Chronicles, vol. 18 – ‘From Some Imaginary Cause’: The Rampage of Irish Canal Workers at Key West in 1831

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

Because Key West is a seaport, outside events have frequently been brought into the community: Ships have arrived for any number of reasons and linked the island city to a larger chain of global and national historical forces that were otherwise unrelated to the Key West story. Oftentimes, groups of people arrived and upended the town’s status quo. Some of these social intrusions were prolonged and broadly consequential like the months-long Mariel boatlift of 1980; others were relatively isolated events like a short-lived town panic caused by the arrival of a ship full of sick people.

One such upheaval happened early in the city’s history, when the ship Maria ran aground on Carysfort Reef, 100 miles distant, in November of 1831. The ship carried a general cargo, but its primary mission was to carry 230 Irish laborers to New Orleans so they could dig canals. Wreckers rescued the group and took them to Key West, where, for reasons unknown, they became irate and went on a rampage, threatening the community’s well-being. Though their visit to Key West proved to ultimately be a minor, if not bizarre, event, it did tie the island to the larger story of Irish immigration, which, in this particular case, changed both the landscape and the culture of the U.S. south.

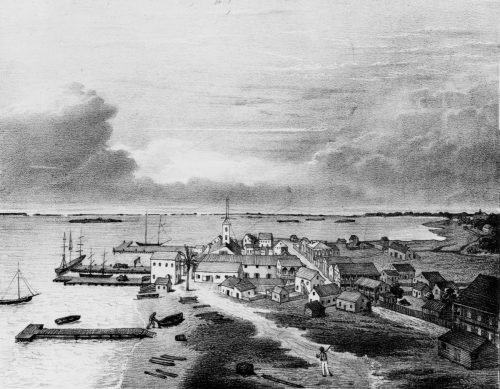

Early view of Key West, Florida. 1838. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Why the Irish?

Though a potato blight and resulting famine in the 1840s is widely regarded as the primary reason for Irish emigration to the United States, Irish immigrants began crossing the Atlantic with regularity beginning in the 1820s, driven primarily by economic pressures and anti-Catholic discrimination. These early immigrants, largely poor men from rural backgrounds, generally did not have enough money to go beyond the port cities at which they arrived. They were also ostracized by most Americans and were offered only jobs that no one else wanted.[1] Their prospects were limited.

Historian Earl Nichaus offers a good explanation of how events conspired to make Irish immigrants the chief source of labor for digging canals in New Orleans.[2] In the 1820s, New Orleans began a period of rapid growth, but the low-lying city was set amongst swamps and lakes that needed to be drained and diked to protect from flooding, and navigable ship channels had to be created to accommodate the city’s expansion. The solution, digging canals and erecting levees, was dangerous, and New Orleans slaveowners were reluctant to risk their human property to the hazards of such “wet work.” It made better economic sense to import cheap labor, and the growing body of Irish immigrants fit the bill. Though an Irishman required a daily wage, the outlay was not comparable to the purchase of a slave. If an Irish laborer drowned or fell victim to disease, the loss was no more than a day’s pay; the loss of a slave was the forfeiture of a significant capital investment.

A quirk of shipping allowed Irish immigrants to be transported cheaply from northeastern U.S. cities to Louisiana. Most freight vessels heading to New Orleans in the early 19th century planned to go there to take on bulky and heavy cargos of cotton, but they also needed a payload for the voyage there. If they could not find freight, people could serve that need, and as a result New Orleans-bound ships were willing to carry Irish workers at a discounted rate to keep their vessels “ballasted” and on an even keel. Labor contractors happily took advantage of the need.

The Wreck of the Maria

Agents for the newly built ship Maria, sailing under Captain Thomas McMullin, began advertising on October 5, 1831, for an upcoming voyage to New Orleans; the vessel was available to carry freight but they planned for it to leave on the 25th “full or not full.”[3] After an unexplained delay, the Maria cleared the port of Philadelphia on November 3, filled with 230 Irishmen, provisions, and a cargo of dry goods.[4] The ship was sighted off Cape Hatteras on November 15, and all was well.[5] Ten days later, though, bad luck struck, and on November 25, Maria ran aground on Carysfort Reef near Key Largo.

Wrecking Captain Jacob Housman of Indian Key, on his schooner Sarah Isabella, aided by a Captain Barker on the schooner Motto, assisted the stricken vessel. First, the crew and passengers were saved, and then divers worked to recover the mostly submerged ship’s equipment, rigging, and cargo. Once they had saved everything they could, the wreckers carried the rescued people and salvaged goods to Key West. The Maria’s hulk was abandoned to the elements.[6]

The two wrecking schooners arrived in Key West (then a town of just over 500 people) on November 30, and 15 to 20 tents were quickly erected for the rescued Irishmen. The Maria’s crew were taken into private homes. Everyone apparently had a quiet first night on the island. But the next day, “after a rather free indulgence in their orisons to Bacchus; they from some imaginary cause became dissatisfied.”[7] As their anger and agitation increased, the Irish workers began to threaten the lives of Captain McMullin and his crew. “By the most boisterous behavior,” their excitement continued into the night, and the island’s residents did not sleep fearing they might be attacked at any moment. But by the early morning hours, as everyone got tired, the wrath faded, and things settled down.

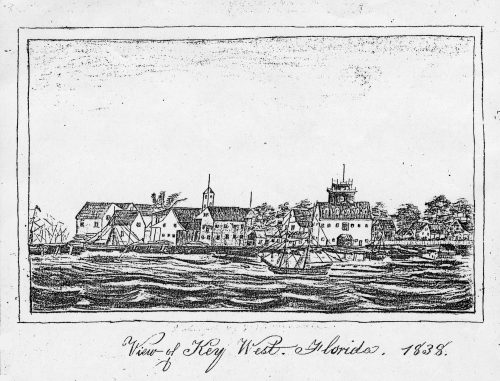

View of Key West, Florida. 1838. Unidentified Artist, FKHC Collection.

The next afternoon the grievances of the Irishmen were reawakened, and the group gathered at F.A. Browne’s wharf as an angry mob. They were so threatening that Browne promptly closed his warehouse there. Soon after, a brawl broke out: “Here a general battle ensued among them in which it was difficult to tell who or how many were engaged, and a disfiguration of the eyes and noses followed, which by no means added to the engaging appearance of the party,” wrote the Key West Gazette. As the violence threated to spread, Key West’s citizenry sent appeals to local military officers requesting help in controlling the angry mob. Their pleas were heard, and an attachment of Marines from the U.S. sloop of war Vincennes landed to guard the warehouses, and Army troops under Lieutenant D.A. Manning patrolled the streets. Order was restored.

Later, after calm prevailed, it came to light that the canal workers were upset with a fellow traveler named Smith, a labor contractor who had stolen money from them. The theft added insult to the injury of the shipwreck and tipped the men into violence. When Key Westers learned of the Irishmen’s grievance, they confronted Smith and forced him to return what he had taken. Of course, the excessive drinking had also inflamed the situation. If the military had not intervened and the money was not returned, “it is more than probable that some serious mischief might have resulted, as the individuals composing the mob were generally under the excitement of liquor during their stay here,” wrote the Gazette. (It says something about 1831 Key West that there was sufficient liquor available to keep 230 men drunk for days.)

On December 3, the Superior Court at Key West heard the case for the salvage of the ship Maria.[8] Judge James Webb listened to testimony for libellants Jacob Housman and his associates, and then that for Thomas McMullin, captain of the Maria. After considering the circumstances, Webb ordered that for the rescue of the passengers and the salvage of the goods, the U.S. marshal sell the Maria’s “tackle, apparel, furniture, and boats” on December 6, and that two-thirds of the proceeds go to the wreckers. The same award applied to the $1455 from earlier sales of the salvaged cargo. The total proceeds are not recorded, but insurers covered any loss, as the Maria was covered by three different brokers for $10,000 by each.[9]

On to New Orleans

The schooner Eliza Williams from Philadelphia had arrived in Key West on December 1 and arranged to take 162 of the Maria’s refugees as passengers. The sloop Signal, carrying twenty-nine enslaved people from Baltimore to New Orleans, made a scheduled stop in Key West, also on December 1, and the captain agreed to take on the remaining eighty survivors of the wreck.[10] On December 6, the two crowded vessels sailed for New Orleans, and they arrived there a week later.[11]

The Irishmen from the Maria were contracted to the New Orleans Canal and Banking Company to work on a new, six-mile canal that would link the city with Lake Pontchartrain. In that endeavor, each man would be paid one dollar for a 12-to-15-hour workday. It would take six years of digging by thousands of men to complete the task, many of whom would die by accident or disease and be buried in muddy graves in the swamplands they were working to conquer. Most of the men survived, though, and many settled in the area, married, and had children. Their descendants live there still, and today New Orleans’ Irish heritage is a large part of the city’s cultural identity. Ultimately, the Key West troubles of the Maria’s men – being shipwrecked, having money stolen, and going on a prolonged drunken rampage – were mere interruptions in their chapter of the great American story.

[1] https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/irish/irish-catholic-immigration-to-america/

[2] Nichaus, Earl F. (1965). The Irish in New Orleans: 1800-1860, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge.

[3] Hollingsworth and Solms (1831). Advertisement, “For New Orleans,” Philadelphia Daily Chronicle, October 5, p.3.

[4] Anonymous a (1831). “For Distant Ports in the United States,” Shipping and Commercial List, and New York Price Current, November 5, p.1.

[5] Anonymous b (1831). “Memoranda,” National Gazette and Literary Register (Phila.), November 23, p.2.

[6] Anonymous c (1831). “Shipwrecks,” National Gazette, December 20, p.2.

[7] Anonymous d (1831). “The Gazette,” Key West Gazette, December 7, p.2. An orison is a prayer; Bacchus was the Roman god of wine.

[8] Admiralty Final Record book for U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Vol. 1 (May 1828-May 1836). Microcopy No. M-1360, Roll1, pp.94-95.

[9] Anonymous e (1831). “More Shipwrecks,” New York Evening Post, December 20, p.2

[10] Anonymous f (1831). “Ship News,” Philadelphia Daily Chronicle, December 30, pp.2-3.

[11] Anonymous g (1831). “Arrived To-Day,” Courrier de la Louisiane, December 14, p.1.

Did you miss any of the earlier volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.

Want to receive future volumes as an email newsletter? You can sign up here.