Island Chronicles, vol. 3: Dr. John Loomis Blodgett, Pioneering Botanist of the Florida Keys

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

In our last edition of Island Chronicles, we published the diary of Henry A. Patterson, a New York hardware clerk who spent four months in Key West in 1843. Patterson kept a detailed account of his experiences in the Florida Keys and wrote of the people he met and associated with. One couple who made regular appearances in Patterson’s journal were a “Doctor Blodgett” and his wife. Patterson socialized with the couple, and he went on adventures with Dr. Blodgett, collecting marine curiosities at Key West, and the two were part of an excursion to Big Pine Key. Patterson described Blodgett as both a physician and a botanist.

Patterson’s “Doctor Blodgett” was John Loomis Blodgett, and a brief biography of him, written by Florida botanist Bruce Ledin, notes that he was born in South Amherst Massachusetts in 1809.[1] He studied medicine at the Berkshire Medical Institution in Pittsfield, Massachusetts from 1827 to 1831. At some point, Blodgett worked with Professor Edward Hitchcock and contributed botanical data to his “Geology of Massachusetts,” which might have been Blodgett’s first formal connection to the study of plants. In 1834, John Blodgett married Julia Smith, also of Massachusetts. That same year the newlyweds moved to Ohio, then to Mobile, Alabama, where John practiced medicine. From there, the Blodgetts made their way to Mississippi, where he became a physician and surgeon for the Mississippi Colonization Society, an organization dedicated to transporting liberated slaves to the West African colony of Liberia.

In the spring of 1837, John Blodgett, in company with other representatives of the Mississippi Colonization Society, sailed to Liberia with a group of freedmen to establish a community named Greenville. Blodgett’s role in the venture apparently varied, as he was listed as Physician, Lieutenant Governor, and Surveyor for the new community.[2] On the group’s arrival to Liberia, Blodgett wrote a long letter giving his impressions of the place. In one passage, his preexistent interest in botany was made clear: “The botanist enters, as it were, upon a new creation; a vast variety of plants are to be numbered that would be quite new to a person from the States; I recognize a few, however, as old acquaintances…” he wrote with wonder.[3]

After spending a year in Liberia, Blodgett returned to the United States, arriving in New York in June of 1838.[4] He made his way back to Mississippi, and the following February he was listed as a member of another planned voyage to Liberia.[5] But Blodgett did not return to Liberia. Instead – exactly when and for reasons that are not known – he went to Key West, Florida.

The Rev. Alva Bennet, rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, had collected plants at Key West when he spent six months on the island in 1834-35, before leaving because of poor health. Given the brevity of his stay coupled with his illness, Bennet’s botanical investigations were relatively slight. When Blodgett came to the island four years later, he undoubtedly found the plants of the Keys fascinating and realized he was presented with an opportunity to conduct significant new botanical research. Blodgett followed Bennet’s lead, and he began collecting plant samples almost immediately after his arrival, a fact demonstrated by a note in In Torrey and Gray’s Flora of North America, Volume I, published in 1840: “The Rev. Mr. Bennet of Genesco New York, presented us with many plants collected by himself during a residence at Key West, and we have received a nearly complete and excellent set of plants of that Island from Mr. J. L. Blodgett, which however reached us at too late a period to receive notice in this volume.”[6] (Blodgett’s specimens were used for Volume II.)

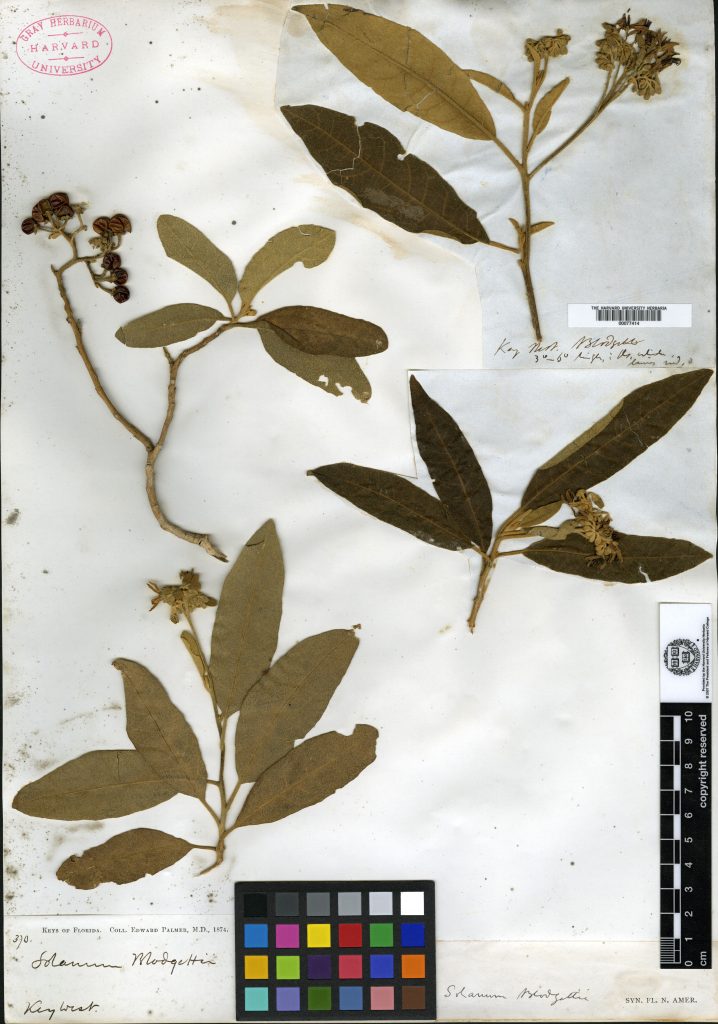

Solanum blodgettii. Named for and collected by J.L. Blodgett at Key West. Harvard Herbaria No. 00077414

John Blodgett was one of the island’s physicians and provided medical and pharmaceutical services to its residents. A later Keys visitor described him this way, “In the first half of the nineteenth century there lived in Key West a Dr. John Blodgett, who practiced medicine and carried on a drug store. He became greatly interested in the botany of the keys and made collecting trips among them.”[7] To the chagrin of the island’s residents, Blodgett’s great interest in botany often superseded his medical practice, and caring for the sick was not always his top priority. Henry Patterson noted in 1843, that when a Key West family experienced a serious outbreak of illness, Blodgett was not there when needed: “Mary Jane also sat up all night. Edwin is getting gradually worse; his life is almost despaired of… Doctor Blodgett is absent, on an excursion up the Reef, in search of curiosities,” he wrote. In fact, Blodgett was often considered a plant scientist as much as a physician. A fact Henry Patterson stated plainly when they set out on an excursion to Big Pine Key, “Doctor Blodgett, being a Botanist, was in search of plants.” Fortunately for the Blodgett marriage, John’s botanical passions became a part of his relationship with Julia – she was a skilled watercolorist and painted many of the plant specimens he collected.[8]

A letter written at Key West by John Blodgett in 1845 has survived, and it details the infatuation he had with plants and the difficulties he was willing to endure in collecting them.[9] Blodgett openly admitted he was obsessed with botany and that it interfered with his medical practice: “… judging from the time that I have spent to the total neglect of business – The expense incurred, the hardship endured & the health exposed I think my taste for botany is above fever heat,” he wrote. And he made clear that his fascination with plants did not come easy; there were many challenges found in the wilds of South Florida. “It is very easy for one to think of making a complete Botanical exploration of Florida but it [is] not easy to put in practice. To do this you must make up your mind to wade, swim & crawl, exposed to a heat of from 120 to 140 degrees excepting a few days in winter your hands well gloved & your face covered with gauze to prevent being devoured by Mosketoes… Add to this the drenching rains, want of shelter at seasons most favourable to making collections loss of your labour as is sometimes unavoidable on account of the weather being unfavourable to the cureing of them and you have some idea of the difficulties to be encountered,” Blodgett explained to his reader.

In 1850, the esteemed Irish botanist William H. Harvey visited Key West to collect specimens of marine algae, and he and Blodgett connected and collaborated in researching Florida Keys seaweeds. “I found Dr. Blodgett a very intelligent person,” wrote Harvey, noting that they collected 130 species of algae in the Keys, many of which were previously unknown.[10] In the introduction to his extensive 1852 study of the subject, Harvey noted, “My friend Dr. Blodgett, of Key West, also, since my return to Europe, has communicated several additional species, and is continuing his researches on that fertile shore.”[11]

Sadly, Blodgett’s research days would not last much longer; his end came not long after Harvey’s volume was published. On May 27, 1853, “JL Blodgett & lady” traveled from Key West to Wilmington, North Carolina.[12] Exactly why they left the island is not known, but it was likely for health reasons, as Blodgett must have been noticeably ill. Shortly after they landed on the east coast, he and Julia made their way to Amherst, where, on July 16, Dr. J.L. Blodgett died of tuberculosis.[13]

John Loomis Blodgett was the first botanist of significance to explore the flora of the Florida Keys and mainland South Florida, and the specimens he collected were crucial new additions to many of the important botanical publications of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Simply put, he was the first person to add a comprehensive assemblage of the plants, shrubs, trees, and algae of the Florida Keys to the annals of science. Because many of the Keys plants he collected were previously unrecorded, several species were named for him. According to biographer Ledin, these include: Ditaxis Blodgetti (Euphorbiaceae or Spruge family), Cyperus Blodgetti (Cyperaceae or Sedge family), named by John Torrey; Metastelma Blodgetti (Asclepiadaceae or Milkweed family), named by Asa Gray; Solanum Blodgetti (Solanaceae or Nightshade family), Paspsalum Blodgetti (Gramineae or grass family), Salvia Blodgettii (Labiatae or Mint family), named by A. W. Chapman; Guettardia Blodgettii (now G. elliptica) (Rubiaceae or Madder family), named by R. J. Shuttleworth; Vernonia Blodgettii (Compositae or Sunflower family), Chamesyce Blodgettii (Euphorbiaceae or Spurge family), named by J. K. Small; Rhus Blodgettii (Anacardiaceae or Poison Ivy family), named by Kearney. In 1858, Blodgett’s friend, the Irish algologist William Harvey, named a new genus of algae “Blodgettia” in honor of his late Key West colleague.

What is perhaps more remarkable is that hundreds of J.L. Blodgett’s botanical specimens have survived and are still with us. Plants that he collected in Key West and the Florida Keys over 175 years ago (including those gathered in 1843 with diarist Henry Patterson at Big Pine Key) are held in many top U.S. and British collections, including the U.S. National Herbarium, the Kew Gardens Herbarium, the Harvard Herbarium, and the New York Botanical Gardens Herbarium. Dr. Blodgett’s specimens continue to serve as principal reference points for today’s botanists studying the distribution and nativity of the plant life of the Florida Keys, the Caribbean, and North America. The “fever heat” still burns.

1845 letter from John L. Bodgett to John Torrey, with transcript

____________________________________________

Note: Many of the botanical specimens collected by John Loomis Blodgett can be seen online. To view the Blodgett collection at the New York Botanical Gardens Herbarium, see here:

Blodgett Specimen List

[1] Ledin, Bruce (1953). John Loomis Blodgett (1809-1853): A Pioneer Botanist of South Florida. Tequesta: Journal of the Historical Society of Southern Florida 1(13):2

[2] “The Colonization Cause in Mississippi,” New York Commercial Advertiser, April 12, 1838,p.1; “Expedition to Liberia,” Connecticut Observer, May 20, 1837, p.2.

[3] “Mission to Africa,” Southern Churchman (Richmond, VA), November 10, 1837, pp.1-2.

[4] “From Western Africa,” New York Commercial Advertiser, June 18, 1838, p.2.

[5] “New Expedition to Africa,” Christian Intelligencer (New York, NY), February 9, 1839, p.3.

[6] Torrey, John, and Asa Gray. A Flora of North America. Vol. I, 1838-1840, Wiley Putnam Co., New York, p.xii

[7] Simpson, Charles Torrey (1922) A Search for Liguus, The Nautilus, 35(3):67.

[8] “The Late Mrs. Julia A. Howe,” Springfield Republican, April 6, 1904, p.14.

[9] The letter, dated October 18, 1845, is in the collection of the New York Botanical Garden and is available online at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/127654

[10] Harvey, Wm. H. (1850). Letter to John Torrey dated April 1. https://archive.org/details/williamhharveyj00harv

[11] Harvey, Wm. H. (1852). Nereis Boreali-Americana, Part I – Melanospermeae. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, p42.

[12] “Arrivals at the Principal Hotels,” Wilmington Daily-Journal, May 27, 1853, p2.

[13] Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth, Boston in FamilySearch database. “Massachusetts, Town Clerk, Vital and Town Records, 1626-2001,” Hampshire > Amherst > Births, marriages, deaths 1844-1891 > image 426 of 562.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Looking to catch up on other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.