Island Chronicles, vol. 4: Caribbean Monk Seals in the Florida Keys

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

In our examinations of old newspapers and other historical documents, we often encounter references to the natural environment of the Florida Keys that once was, including wildlife that no longer exists. One animal that appears with some frequency in the historical record is the Caribbean monk seal. Archaeological evidence shows seals were part of the Keys ecological system thousands of years ago, and remarkably, historical narratives reveal that they are not-so-long-gone: Until about 100 years ago, seals could still be found swimming in Keys waters and lounging on local sandy shoals. Ultimately, like so many other environmental stories, piecing together the various accounts of Keys seals reveals a great tragedy in natural history.

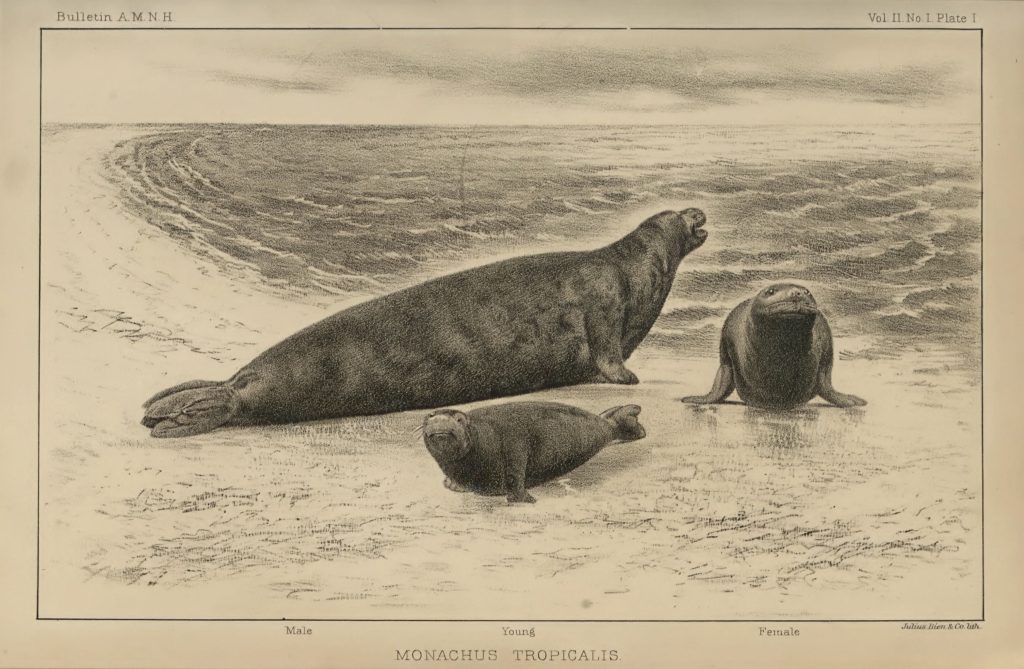

The Caribbean monk seal (Monachus tropicalis) was one three species of monk seal, along with the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) and the Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi), both now critically endangered. Caribbean seal colonies ranged from Hispaniola to the Nicaraguan coast, around Yucatan to the eastern coast of Mexico, then across to South Florida, the Bahamas, and the Turks and Caicos Islands (Timm, Salazar, & Peterson, 1997). In the grand scheme of seals, they were medium-sized, with adults seven to nine feet long. Caribbean monk seals were covered short, brown fur that became lighter on the sides; newborns had long, soft, black fur (Allen, 1890:4-5).

Physical evidence reveals that in prehistoric times, monk seals were by exploited Florida’s indigenous peoples. A 1,400-year-old seal bone was found in a Native American archaeological context at Pine Island in Lee County (Walker, 2005) and a tooth was found at a 500-1000-year-old site at Lake Worth in Palm Beach County (Kleinberg, 2016). Seal bones and teeth found at an early site on Stock Island show that monk seals were hunted and eaten by native Keys residents in the 2,000-year period running from roughly 500 BCE to ca 1500. (Harke, 2021:284).

The colonial period looks to have been the tipping point for the decline of Caribbean monk seals as the they were apparently easy to approach and easy to kill, and after colonization they were taken in great numbers as food and for their fat. The first European encounter with Caribbean seals in August of 1494, presaged the decimation. It occurred during Christopher Columbus’ second voyage, after they anchored ship at a small island near Hispaniola and men were sent on shore to explore. There “they killed eight seals which were sleeping in the sand” (Keen, 1934:144). Over the next 300 years, things only got worse, and by the turn of the 19th century the Caribbean seal population had dropped dramatically from its original numbers. In the late 1800s, the American naturalist Dr. Joel Allen wrote, “…it appears to have now well-nigh reached extinction and is doubtless to be found at only a few of the least frequented islets in various portions of the area above indicated” (Allen, 1880:722).

Taking ‘sea wolves’ at the Tortugas

The first historical account of seals in the Florida Keys comes from the voyage of Juan Ponce de Leon, which says, “…on Tuesday the twenty first, they arrived at the islands that they named the Tortugas, because in one night they took one hundred and sixty turtles on one of these islands, and could have taken many more if they wanted, and they also took fourteen ‘sea wolves’ (lobos marinos)” (Herrera y Tordesillas, 1601:304). A few decades later, Hernando D’Escalante de Fontaneda, a shipwrecked Spaniard who was held captive for 16 years by the Indians of the Florida Keys, wrote that seals served as a luxury food for the native islanders: “Some eat sea wolves; not all of them, for there is a distinction between the higher and lower classes, but the principal ones eat them” (True, 1944:26).

Largely because of a lack of European presence, not much is written about the Keys in the 17th century, but when the British Royal Navy Frigate HMS Tyger wrecked at the Dry Tortugas in 1742, the stranded crew lived on the remote islands for over two months, and the detailed, daily documentation they kept during their ordeal shows seals formed a large part of their diet. A typical entry in the ships log reads: “Friday Feb. 12. …At 4 am launched the small canoe and sent her to the windward keys to kill seals. …At 10 D:o returned the canoe with six seals that were served to the ship’s company” (Viele, n.d.: 10). A few years later, in 1763, the English cartographer Thomas Jeffreys surveyed and described the Florida Keys and said, “On the La Sonda, north of the Tortugas, there is a very good fishery…it also abounds with great plenty of seals, the fat of which the Spaniards pay the bottom of their ships with at Havana” (Roberts, 1763: 18-19). This “fishery” looks to have devastated what was likely a tenuous seal population, and, for over a century, none were noted in the Florida Keys. But in 1878, an R.W. Kemp wrote a letter from Key West telling of an encounter he had had with two seals at Cape Florida some two or three years earlier, creatures he suspected had come from the Bahamas. Kemp noted that monk seals had indeed become scarce in Florida, saying they were seen “only once or twice in a lifetime” (Allen, 1880: 721-722).

The last seal sightings in the Keys

Seals lived in the Florida Keys into the 20th century, though, and an interesting story of a group residing at the Dry Tortugas in the early 1900s comes from a 1951 letter by C.R. Vinten, then the coordinating superintendent of Southeastern U.S. National Monuments. Vinten wrote, “In 1939, I was at Fort Jefferson when Everett P. Larsh of Dayton, Ohio, arrived in his yacht. He was once the army radio operator at Fort Jefferson, 1903-1908. Upon coming ashore one of his questions was, ‘Are there still any sea lions around here?’ …I drew out the information from him that during his army tour there were several ‘sea lions’ on nearby islands; that he and some of his friends caught two in a net and screened the moat openings and kept them in the moat where they became fairly tame (Moore, 1953:118-119).

At much the same time that Everett Larsh was using the Fort Jefferson moat as a holding pen, a seal was encountered near Key West in February of 1906, and the incident is well documented. The Daily Miami Metropolis reported, “Sunday, a party of young men went out for a cruise and a fish. While in Jewfish channel they saw a large object in the water and on getting near to it struck it with a pair of grains. It proved too much for the five men in the dinghy and pulled them around at a five mile gait. Finally, it made a charge on the dinghy and seeing it would be impossible to land it alive, the men shot it and towed it to the large boat and brought it to Key West. The seal measured eight feet and weighed 800 pounds. It is on exhibition on Front Street and a large crowd have paid an admission of ten cents to see it. The strange fish had no hair but in all other respects resembles the seals caught in Alaska. These seals have been seen around Dog Rocks and this one, no doubt, strayed away from there” (Anonymous a, 1906: 8). The Jacksonville Florida Times-Union added, “The seal had been seen several times in the vicinity of Key West on the reef, on sand bars, and at Tortugas and Sand Key Lighthouse” (Anonymous b, 1906). Charles H. Townsend, director of the New York Aquarium was able to evaluate the skin and skull of the seal, which were being kept in a home on Virginia Street. Townsend reported that the seal was a female of the species monachus tropicalis, nine feet long, and estimated to be 30 years old, as its canine teeth were worn flat to the same level as its other teeth. He also noted that it was the first of its kind to be seen at Key West in approximately 30 years and that, in general, West Indian monk seals had practically disappeared, though, he added, they could then still be found on the “Triangle Islands” (Arrecife Triángulos) in the Bay of Campeche (Townsend, 1906).

Assuming the reported locations for the 1906 Key West monk seal are accurate, they shed light on the range of the species in the Florida Keys. The seal was killed at Jewfish Channel, approximately 7 miles north-northeast of Key West, where the sandy banks and mangrove islands of the Keys meet the Gulf of Mexico. The same creature was reportedly seen at the Dry Tortugas, 65 miles west of Key West, and Sand Key, 8 miles south-southwest of the island city. And if the seal did indeed come from a population at Dog Rocks at the northern edge of the Cay Sal Bank, some 125 miles east-southeast of Key West, this one individual had traveled considerable distances throughout the greater Florida Keys region. Additionally, the combined information from the two early-1900s Florida Keys encounters shows that that trace colonies of monk seals persisted at the Dry Tortugas, Cay Sal Bank, and the islets of Campeche into the 20th century.

It would be another 16 years before another monk seal was seen near Key West. Unfortunately, it was also killed. No news accounts have been found about the encounter, only a brief report by the New York Aquarium’s Charles Townsend that says simply, “A specimen was killed on March 15, 1922, near Key West, Florida, where it was identified by Mr. L.L. Mowbray, formerly of the Aquarium staff” (Townsend, 1923). This was the last documented sighting of a seal in the Florida Keys.

Despite a lack of sightings, some people still held out hope the seals could make a comeback. The U.S. National Park Service zoologist Joseph C. Moore had a particularly interesting idea that might have had merit. Writing in 1953, he said he had been told of a small colony of Caribbean monk seals that still existed in an undisclosed location. He thought that if he could capture some of these seals and transport them to the Dry Tortugas, they could be protected there under its U.S. National Monument status and form a breeding colony (Moore, 1953: 120). Unfortunately, Moore’s idea came too late. The last confirmed sighting of Caribbean monk seals was in 1952, at the remote Seranilla Bank midway between Jamaica and Nicaragua (Rice, 1973). Subsequent surveys across the seals’ historic range in the 1970s and 1980s yielded no evidence of their existence, and it became apparent that they were most likely gone (Kenyon, 1977; LeBoeuf, Kenyon, & Villa Ramirez, 1986). In 2008, after an extensive five-year review, the Caribbean monk seal was removed from the endangered species list and officially declared extinct by the U.S. government (National Marine Fisheries Service & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2008). Barring a literal miracle, they will never be seen again.

Bibliography

Allen, Joel A. (1880). History of North American Pinnipeds, Dept. of the Interior Misc. Publications No.19. Government Printing Office, Washington DC.

Allen, Joel A. (1890). The West Indian Seal (Monachus tropicalis Gray). In Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume II, pp.1-34. Printed for the Museum, New York.

Anonymous a (1906). “Key Westers Kill a Seal,” Daily Miami Metropolis, February 28.

Anonymous b (1906). “Key West News Notes,” Jacksonville Times-Union, March 2.

Harke, Ryan M. (2021). Archaeology and Seasonality of Stock Island (8Mo2), a Glades-Tradition Village on Key West, PhD dissertation, University of South Florida, Department of Anthropology.

Herrera y Tordesillas, Antonio (1601), Historia General de los hechos de los castellanos en las Islas y tierra firme del mar Océano, Decada I, Libro IX. Imprenta Real, Madrid.

Keen, Benjamin (translator) (1934). The Life of The Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick.

Kenyon, Karl W. (1977). Caribbean Monk Seal Extinct. Journal of Mammalogy, 58(1): 97-98.

Kleinberg, Eliot (2016). Prehistoric Seal Tooth found in Palm Beach, Palm Beach Post, December 15. www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/local/2016/12/15/prehistoric-seal-tooth-found-in/6993898007/

LeBoeuf, B.J.; Kenyon, K.W.; & Villa Ramirez, B. (1986). The Caribbean Monk Seal is Extinct. Marine Mammal Science, 2(1):70-72.

Moore, J.C. (1953). Distribution of marine mammals to Florida waters. American Midland Naturalist, 49(1): 117-158.

National Marine Fisheries Service & National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2008). Final Rule to Remove the Caribbean Monk Seal from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Federal Register, Vol. 73, No. 209, pp.63901-63907.

Rice, Dale W. (1973). Caribbean Monk Seal (Monachus tropicalis), paper No.12, Proceedings of a Working Meeting of Seal Specialists on Threatened and Depleted Seals of the World, held under the auspices of the Survival Service Commission of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 1110 Morges, Switzerland.

Roberts, William (1763). An account of the first discovery, and natural history of Florida. London. purl.flvc.org/fcla/dt/2760144

Timm, Robert M., R.M. Salazar, A.T. Peterson (1997). Historical Distribution of the Extinct Tropical Seal, Monachus tropicalis (Carnivora: Phocidae), Conservation Biology, 11(2):549-551.

Townsend, Charles H. (1906). Capture of the West Indian Seal (Monachus Tropicalus) at Key West, Florida. Science 23(589):583.

Townsend, Charles H. (1923). The West Indian Seal. Journal of Mammalogy, 4:1(55).

Viele, John (n.d.) Transcript of the Log of the H.M.S. Tyger, January to May 1742. Gail Swanson Papers, Florida Keys History Center.

Walker, Karen J. (2005). Pineland Mystery Bone is from Monk Seal. Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter 4(1):1-2.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Looking to catch up on other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.