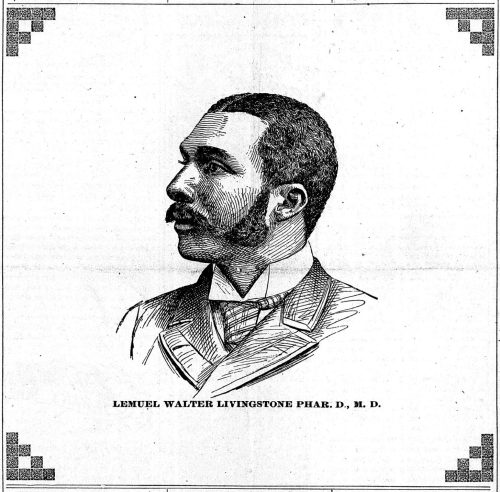

Island Chronicles, vol. 6: Dr. Lemuel Walter Livingston – An Early Principal of Key West’s Douglass School, and the Island’s First Black Physician

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

On September 22, 1888, a young doctor named Lemuel Walter Livingston left Washington, DC, to take the position of principal at the Douglass School in Key West. Though he had not been to the island before, Livingston was certainly familiar with the place as he had been the DC correspondent for the “Key West News,” a paper published by the abolitionist, author, and politician John Willis Menard. Menard had previously served as principal of the Douglass school and was likely influential in Livingston’s decision to come to the island.

According to a brief biography written by his friend, Judge James Dean of Key West,[1] Livingston was born in Monticello, Florida, northeast of Tallahassee, on May 1, 1861. At the conclusion of the Civil War, he was old enough to attend a school run by the Freedmen’s Bureau. At the age of seventeen, after a break in his schooling to tend to the family farm, he became a teacher in Madison County. In 1879, Livingston began coursework at the Cookman Institute in Jacksonville, and he graduated from there in 1882.

Livingston then applied for an appointment at West Point, and, after much public indignation and racially prejudiced outcry against his nomination, he was allowed to take the examination. Livingston traveled to the Military Academy, and his visit was documented: “Among them is the colored applicant from Florida, Lemuel W. Livingston. He is described as nearly six foot in height and jet black…. Dr. Alexander, examining surgeon, says he has a fine physique and a bright and intelligent face…. Some of the officers speak in a highly complimentary manner of his physique and general appearance. It is believed he will pass the required examination.”[2] The examiners said Livingston did not pass the math portion of the assessment, a subject he had excelled at in his earlier studies, and he was denied admission.

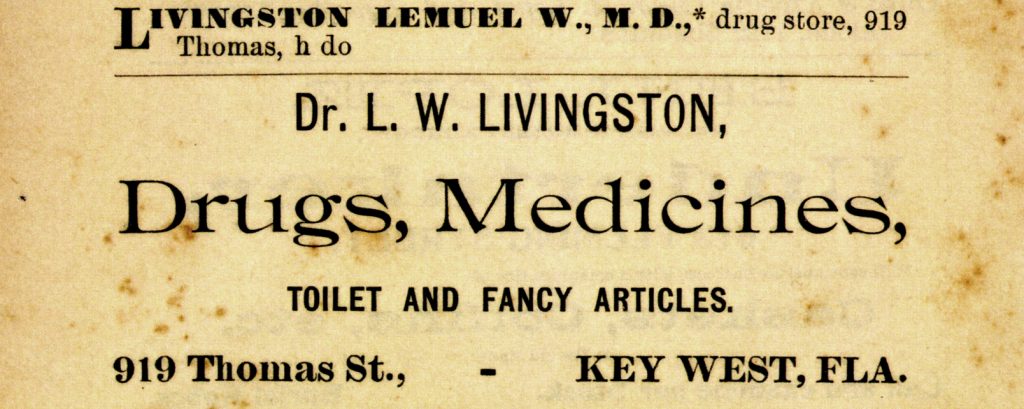

Not one to be thwarted, Livingston became a clerk with the Treasury Department and almost simultaneously began medical studies at Howard University. After completing his studies and being awarded a medical degree, Livingston then entered the pharmacology program, and in 1888, he received his Doctor of Pharmacy degree. Later that year, Livingston resigned his Treasury position and moved to Key West, at the urging of his friend and fellow Howard graduate James Dean. Dean had taken the Douglass principalship the year before, but his growing law practice made it impossible to continue. Livingston took on the burden of dual careers, and aside from his new role as principal to the 400 students at the Douglass School, he also became the island’s first Black physician and pharmacist. In his role as doctor, Livingston ran the “Subtropical Drug Store” at 919 Thomas Street, with his medical office above the store (Figure 2).

By all accounts, Livingston was an effective and respected educator. As Dean wrote, “As the principal of the Douglass School, he has ever since ably stood at the head of the educational work of his race in Monroe County.” Three years later, in 1894, another person said of the school’s success, “Too much credit cannot be given to Dr. Livingston – the principal – and his excellent staff of teachers for their zeal in the education of the youth of our city. In all branches the students showed a proficiency.”[3]

Though specifics are scant about Livingston’s medical practice it was said he had “a large practice among both white and colored.”[4] Livingston was particularly important to Key West’s Black community because he was the first African-American doctor on the island, and he lived and worked in the heart of the traditionally Black section of the town. Few details of his practice have survived, with only one account of his emergency services reported by the Key West Equator-Democrat newspaper: After two men got into a knife fight on Thomas Street, with one slashing the other, Livingston was nearby and quickly available to treat the wounds.[5]

Livingston continued his role as newspaper correspondent and submitted columns about Key West to northern, Black-oriented publications. He documented his voyage immediately after his arrival and made note of the island’s cosmopolitan populace, a theme that would persist throughout all of his writing: “Of its much mixed population, embracing Americans of all complexions from white to the opposite extreme, Cubans, Bahamians, and the heathen Chinese, I hope to write in the future,” he noted in a letter written on his second day at Key West.[6] Three weeks later, Livingston continued, “We are on a little island here, cut off from the rest of the world, both civilized and uncivilized, and absolutely dependent upon Havana, New Orleans, Tampa and New York, especially the last-named place…. But the greatest peculiarity of the place is in the population and their mode of life. There is such a conglomeration of American colored and white folks, Cubans, colored immigrants from Nassau and Conchs, and such an admixture of them all that it is impossible to determine where the line begins and where it ends.”[7]

The way in which the islanders intertwined socially and politically also impressed Livingston. Though the various groups certainly maintained divisions along ethnic lines, there was a tolerance, perhaps a result of the narrow geographic constraints, that, to him, was unlike any other place in the United States. And, as he saw it, the inspiring part of this freedom was not just the openness, but the way in which people of color could confidently assert their strengths. Livingston described the situation thusly, “Key West is the freest town in the South, not even Washington excepted. There are no attempts at bulldozing and intimidation during campaigns and elections here. No Negroes are murdered in cold blood, and there are no gross miscarriages of justice against them as is so frequently seen throughout the South, to her everlasting shame and disgrace. The white Americans here are very different apparently from their brothers across the gulf. There are a few fire eaters in a quiet way, but the majority of them seem civil and respectful. The colored men are manly and courageous, well-equipped with the means of offensive and defensive warfare, as conducted in times of peace with a good sprinkling of old soldiers among them, and the beauty of the whole affair is that they are not the only ones that knows their power and invincibleness.”[8]

Indeed, post-civil War Key West was a relatively progressive place. In the 25 years after the war, and with the rise of the Republican party of Lincoln and Grant, men of African descent held public office on the island, including ten men on the city council; John Cornell, Sr. served as city clerk in 1875-76; Frank Adams served as tax assessor from 1886-1889; Charles Shavers was elected to the state legislature in 1886; and in 1888, James Dean was elected judge for Monroe County, along with Charles DuPont as Monroe County Sheriff. And Cubans, who had emigrated to the island in the post-war years, also successfully entered the political arena: In 1876, Carlos M. de Cespedes was elected mayor, and in 1884 Fernando Figueredo was elected state legislator and later served as county school superintendent.[9] To someone like Livingston, just arriving to such an egalitarian community, Key West must have been a wondrous place. But the pressures of racism seeped through: Judge Dean was removed from office in 1889, for having overseen the marriage of a “mixed race” couple.

Livingston himself became involved in politics and was an active member of the Republican party. In 1896, he was elected as a Florida delegate to the Republican convention at St. Louis, but it was a contested appointment. Florida had two factions of delegates that year at its party convention in Tallahassee. The regular delegates, who held 150 of 230 seats, and of which Livingston was one, were supportive of McKinley. An opposing 80 delegates were anti-McKinley and were known as the “lily whites,” because they wanted to remove all Black representation and management from the Republican party.[10] The majority prevailed, though, and Livingston went to St. Louis. He voted for McKinley and endorsed a platform that included support for a Cuba free from Spanish rule and a Nicaragua canal linking the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea.

Livingston returned to Key West, but his involvement in politics and support for McKinley changed the course of his interests. His role as national delegate involved him further in matters in DC. In March of 1897, Livingston traveled from the island to Washington as one of 20 representatives of the African Methodist Episcopal Church who presented the new president with a custom-made Bible; the one he would be sworn in with. By May, Livingston’s political goals were taking him well beyond Key West’s Douglass School and his medical practice, and he applied for the position of U.S. Consul at Valparaiso, Chile.[11]

It is not clear if Livingston’s desire for a change was driven solely by personal ambition, or if the handwriting was on the wall for a changing racial climate at his Florida home. In June of 1897, Key West would experience a “race riot,” triggered by the attempted lynching of a Black man, Sylvanus Johnson, who had been accused of assaulting a white woman. When white vigilantes attempted to remove Johnson from the jail to hang him, they were rebuffed by a group of armed Black men, and one of the whites was shot and killed.[12] A witness at the time said, “The entire town is under arms, and the white and colored populations are watching each other with jealous eyes.” In this climate of tension and mistrust, Johnson was soon tried, convicted, and hanged. Clearly, Key West was no longer the harmonious racial melting pot that Livingston felt it was when he first arrived.

Livingston’s consular ambitions were also thwarted by racism. Though Black supporters of McKinley had been told they would be favorably regarded for positions in the administration, the tone changed after the inauguration. Livingston had applied directly to Secretary of State John Sherman for the diplomatic post, but Sherman told him he was worried the Chilean government might not be so open to a Black consul.[13] After much foot-dragging by Sherman, Livingston was told Chile would not be receptive to having him there. Instead, Livingston was offered the job of Consul at Cap-Haïtien in Haiti at a salary of $1,000 per year.[14] He accepted, and on January 14, 1898, his appointment was confirmed by the Senate.[15]

Much of what is known about Livingston’s time in Haiti comes from diplomatic correspondence and covers political, economic, and U.S. interest in the country, but he apparently enjoyed his position as Consul, and after 21 years of service he retired in December 1919. Long-time friend James Weldon Johnson wrote of a visit to Haiti, where he visited the recently retired Livingston: “Up to a short time before, he had been the American Consul at Cap-Haïtien, having served about twenty years at the same post. He had also during nearly all that time been the correspondent of the Associated Press.”[16] Johnson also noted that, “He had married a charming Haitian woman, whose father, I learned, was a man of some wealth. Livingston’s marriage furnished his main reason for never wishing to be transferred from Cap-Haïtien.” Apparently, though, they did not have children. Lemuel Livingston died in Haiti on December 18, 1930.

Lemuel W. Livingston made his mark on Key West: He was an influential figure to the many hundreds of young people who attended the island’s Douglass School under his principalship, and he will always be remembered as the city’s first Black physician and pharmacist. In a broader sense, Livingston’s story is inspirational in that he demonstrated, again and again, the will to find a way forward no matter the obstacles that were placed in his way. It is men like him who have made a positive difference in the world, even if the world was not always ready for them.

Appendix: Newspaper columns written by Dr. Lemuel W. Livingston at Key West, 1888-1890, transcribed

[1] Dean, James (1891). “Dr. L.W. Livingstone,” The Appeal (Minneapolis-St. Paul), 7 March, p1.

[2] Anonymous (1882). “West Point.” Army and Navy Journal, September 2, p107.

[3] Key West Equator-Democrat, July 2, 1894. As quoted in Brown, Canter Jr. (2006). Dr. James Alpheus Butler: An African American Pioneer of Miami Medicine, Tequesta, 66(2):49-81.

[4] R., Geo. B. (1890). “A Beautiful City,” The Freeman, November 29, p1.

[5] Anonymous (1890). Savannah Morning News, “Key West Equator-Democrat,” October 11, p7.

[6] Livingston, Lemuel W. (1888). “From New York to Key West,” New York Age, October 13, p1.

[7] Livingston, Lemuel W. (1888). “The Peculiarities of Key West,” New York Age, November 3, p1.

[8] Livingston, L.W. (1888). “Freest Town in the South,” New York Age, November 24, p1.

[9] Brown, op.cit.; Browne, Jefferson B. (1912). Key West, The Old and The New, The Record Company, St. Augustine, p118.

[10] The Evening Star (1896). “Florida,” March 14, p18.

[11] The Appeal (1897). “Washington. The City and Its Happenings,”, May 1, p1.

[12] New York Herald (1897). “A Race War in Key West,” June 26, p1.

[13] New York Herald (1897). “Negroes and The Offices. Dissatisfaction with the Administration’s Course,” May 17, p3.

[14] The Freeman (1897) “Another Consulship Landed,” December 11, p1.

[15] The Evening Star (1898). “Judge Kimball Confirmed. Favorable Action by the Senate on Many Nominations,” January 15, p9.

[16] Johnson, James Weldon (1933). Along this Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. Viking Press, New York, p350.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Looking to catch up on other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.