Island Chronicles, vol. 7: Across the Bridges and Over the Ties – A Pioneering Drive to Key West in 1927

Welcome to “Island Chronicles,” the Florida Keys History Center’s monthly feature dedicated to investigating and sharing events from the history of Monroe County, Florida. These pieces draw from a variety of sources, but our primary well is the FKHC’s archive of documents, photographs, diaries, newspapers, maps, and other historical materials.

By Corey Malcom, PhD

Lead Historian, Florida Keys History Center

In the period between World War One and the stock market crash of 1929, there was the decade known as “Roaring ‘20s,” when the economy boomed, and social boundaries expanded. People across the U.S. were riding high and feeling good. That collective exuberance was often expressed in fads, stunts, and endurance contests: flagpole-sitting, dance marathons, and aviation feats like barnstorming and wing-walking were characteristic of the decade. And as media consumption grew with increasing newspaper and radio coverage, along with the dawning of the newsreel era, these exploits were tantalizing fodder for expanding media markets. Though many of these feats were aimless and done just to be done, they could sometimes be prescient and signal new horizons. One 1927 stunt, seemingly a gimmick on the surface, helped usher in a new era of Florida Keys travel: On December 23 and 24, a forty-three-year-old Jacksonville car dealer named Claude Nolan, assisted by race driver Kenneth Goodson, drove from Miami to Key West. It was the first time an automobile would make the island-hopping journey.

The Keys became a part of the U.S. in 1822, and at the same time began to be settled. For the next 90 years, the only way to access the islands was by boat. That changed when Henry Flagler began to build his Overseas Railroad in 1906, which then, bit by bit, pushed down the Keys until it reached Key West in 1912. With that, the entirety of the island chain was accessible by a route other than the sea. By the 1920s, as South Florida began to be widely settled, roads were being carved across the peninsula for increasingly popular and available automobiles. The Dixie Highway, which connected the Midwest to the South, went as far south as Florida City, but pressure grew for there to be some way for people to drive to and through the Florida Keys.

The beginnings of the Overseas Highway

Construction of what would be dubbed the “Overseas Highway” started in August of 1924. Over the next three and a half years, a route took shape that ran from the mainland to Lower Matecumbe Key. There, it ended in a ferry terminal. Cars could then be transported by boat to No Name Key, where the road resumed and connected to Key West.

When Claude Nolan made his drive, the highway was essentially finished, but the ferries to make the Matecumbe-to-No Name crossing had not yet been delivered. There was a 50-plus-mile water gap, and the only way to drive to Key West was to cross on the railroad bridges. For Nolan, that was the appeal.

In 1907, Claude Nolan established the first automobile dealership in Jacksonville and the first Cadillac franchise in the South.[1] Nolan was a self-promoter and no stranger to out-of-the-box thinking and adventure. In 1908, he participated in a Jacksonville-to-Miami automobile race and managed to come in second place after a 48-hour run in his 10-horsepower Cadillac.[2] In 1910, he became the first Floridian to fly over Florida soil in an airplane.[3] And in 1923, he gained national notoriety when he, with the help of Capt. Newton Knowles of Miami, caught a massive, rarely-seen “Rhynodon” (whale shark) near Marathon in the Florida Keys. Claude Nolan’s dramatized version of the capture – complete with a battle with tiger sharks over the bloody carcass – was published in papers across the country.[4] To further enhance his feat, Nolan donated the shark’s remains to the American Museum of Natural History, and a model of it was created for display.[5]

The construction of the Overseas Highway was a relatively exotic undertaking, and its progress was making news at the time. When friend and automobile racer Kenneth Goodson proposed they drive to Key West before the ferries were in place and over the railroad bridges, Nolan was enthusiastic; he decided to throw his resources into making it happen. He saw such a drive as not only a great publicity stunt, but also a great adventure: “No more difficult and perilous test has ever been undertaken by car and driver,” he declared.[6] Nolan’s other goal for making the drive was to promote the cars he sold. Cadillac had just launched the new, budget-friendly LaSalle line, and he wanted to prove the quality of the new make. “We have two outstanding reasons for making such a trip. We want to carry the first motor car into Key West under its own power, and we are very anxious to determine how the car will stand up under such a grueling test,” he said.

For a month, the two men planned the drive.[7] First, they contacted the railroad to make sure they would allow the use of their tracks. They met with Henry N. Rodenbaugh, vice-president and general manager of the Florida East Coast railway, and he approved of the idea. As he saw it, the drive over the bridges would bring attention to the railroad’s business, too.

Calculations about the logistics of driving on the tracks were made. The plan was to make the journey with an unmodified, stock model LaSalle. The LaSalle would mount ordinary balloon tires, which would give it a track nearly as wide as that of a railcar. This meant that two of the LaSalle’s wheels would have to run outside of the rails, with the other two between. Because the wooden ties extended roughly ten inches beyond the rails, and the tires were six inches wide, there would be four inches of leeway before the outside wheels went over the water. This required one alteration to the vehicle – the front fender on the driver’s side was removed, so the drivers could see how close to the edge the wheel was running. Another challenge was that the gaps between the ties would make the car bounce, and the men calculated that they would have to travel at 40 miles an hour to lessen the effect and better maintain control. Still, jostling and shaking would be unavoidable, so they planned to switch drivers every 15 minutes to prevent fatigue. They would also wear bathing suits and life preservers in case they fell into the water.

The men were ready to go on December 19, but their drive was delayed by a week because motion picture crews scheduled to film the feat were held up in Daytona, waiting to film an endurance flight that was running behind schedule. At last, on December 23, all the pieces were in place. At 7:45 in the morning, Nolan and Goodson met Miami Mayor E.G. Sewell at the FEC depot for a departure ceremony, and he gave them a letter to deliver to Key West Mayor Leslie Curry. A short train with a locomotive, coach, and flat car carrying a rescue team, journalists, and the newsreel crews was also there.[8] At 8:10 a.m., the men left the depot to begin their drive down the Overseas Highway, and they covered the 96 miles to Lower Matecumbe Key in an impressive hour and fifty minutes.

At Lower Matecumbe, they reached the point where the highway ended; it was time for Nolan and Goodson to put the LaSalle onto the railroad tracks and “take to the ties.” Just like a train, their vehicle was put on the railroad’s timetable, and their scheduled right-of-way was designed to not conflict with the Havana Special that still had to get through. Before the LaSalle left the highway for the tracks, the small support train went ahead, so the observers and film crews could have a better view of the vehicle.

The wind was stronger than they had expected, but they managed to successfully cross the Channel 2 and Channel 5 bridges soon after they started. When the men reached Long Key, they stopped for lunch aboard Nolan’s yacht, which had arrived earlier. After the break, they got back on the tracks to face their next challenge – the Long Key Viaduct – a 2½-mile crossing over open water. Spectators, on boats running alongside the viaduct, cheered for the drivers as they bumped across the ties. The fear of falling into the choppy seas almost came to pass when the car hit an errant plank, and the rear left wheel went over the side. Newsmen gasped as they watched in horror from the train, but Nolan successfully maneuvered the LaSalle to set the wheel back onto the bridge.

The drivers arrived in Marathon at 2 in the afternoon. There, they had to pull over onto a siding for over an hour to let an off-schedule passenger train through. After the men got going again, they picked up speed, at one point hitting 47 miles per hour as they neared Knight’s Key. They were slowed again, though, when they encountered culverts that forced them onto the shoulder of the railway. Half a dozen railroad workers stood on one running board to keep the LaSalle from slipping down the embankment. After it had safely cleared the obstacles, another half dozen men helped get it back onto the tracks.

From Knight’s Key, Nolan and Goodson encountered their biggest challenge – a seven-mile, open-water crossing, interrupted only by tiny Pigeon Key. They made it without incident to the island. There, though, with darkness falling fast, it became apparent they would no longer be able to see the edge of the bridge. It was unsafe to proceed. The men were also quite tired from their daylong stressful drive, so they decided to call it quits for the night. As the children of Pigeon Key, most of whom had never seen an automobile, clambered over the strange, new machine, Nolan and Goodson boarded the small train that accompanied them and headed to Key West for a meal, a bath, and a good night’s sleep.

A perilous place to change your tires

At 6 In the morning, the train left Key West for the return to Pigeon Key, and it arrived there at 8. Within 20 minutes, Nolan and Goodson were once again behind the wheel and headed toward Big Pine Key to complete their journey. Though the weather was quieter than the day before, they quickly ran into another problem. There was a guard rail that forced them to drive close to the track, which made the wheels rub against the railroad iron. Already weakened from the previous day’s pounding, the tires began to fail, and three went flat while on the bridge. Fortunately, the men carried six spares, but to the change the bad tires, Ken Goodson had to wear a rope harness and hang over the side, 40 feet above the water. Once they had made their repairs, cleared the bridge, and made it to land, the fourth of their original tires went flat. After it, too, was changed, they carried on across smaller bridges and keys with all new rubber. Shortly after 1 in the afternoon, they arrived at Big Pine Key.

A motorcade with a delegation from Key West had arrived to greet the drivers at Big Pine, and the entourage began heading toward the island city shortly after 2. Since they were back on the Overseas Highway and no longer had to travel on the railroad, this last push was a smoother and faster ride. At Stock Island, an escort of police motorcycles met them and led the LaSalle into Key West. Nolan decided that since they had started at a railway station, they should end at one, too, so they steered to the Florida East Coast Railroad depot at Trumbo Point. There, on December 24, 1927, the first car to drive from the mainland to Key West completed its journey at 3:15 p.m. The letter from Miami was handed to Mayor Curry, making it the first message to be delivered to Key West by automobile. Claude Nolan’s goals were met, as the LaSalle held up as he had hoped: “Press representatives tell me that they marvel at any automobile being able to undergo such a test without the replacement or adjustment of any part except tires,” he bragged.[9] And his stunt generated much publicity, too. Stories about the drive were featured in over 2,000 newspapers, with a combined circulation of over one million.

Soon after the pioneering drive, regular traffic would begin to traverse the Overseas Highway. The ferry to transport cars across the water gap arrived on January 13, and it carried its first passengers two days later. The grand opening celebration for the highway was held on January 25, 1928, and with that automobile travel through the Florida Keys began in earnest. Ten years later, in 1938, after the highway took over the railroad’s right-of-way, bridges and all, automobiles could at last replicate that first, pioneering drive, albeit in much greater comfort.

A crazy, daring stunt by Claude Nolan and Ken Goodson, intended primarily to sell cars, instead proved to be prophetic. Their attention-grabbing drive called attention to the shifting possibilities of automobile travel, and for the Florida Keys their adventure proved to be the leading edge of a trend. Today, for Florida Keys residents and visitors alike, travel along US 1 by car is the predominant form of transportation through the island chain. On average, over 25,000 vehicles utilize some portion of the Overseas Highway every day.[10] Sometimes gimmicks prove to be more than they appear.

[1] City of Jacksonville (n.d.). Report of the Planning and Development Department Application for Designation as a City of Jacksonville Landmark: LM-13-05, 937 N. Main Street, The Claude Nolan Cadillac Building and Garages.

[2] Anonymous (1908). W.M. Stinson wins Road Race, Daytona Gazette News, March 21, p.2.

[3] City of Jacksonville, op.cit.

[4] See Public Ledger Company (1923). “Carried off to sea by a 15-ton shark,” Columbus (OH) Dispatch, July 22, p.63.

[5] Gudger, E.W. (1933). The Fourth Florida Whale Shark, Rhinodon Typus, and the American Museum Model Based on it. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 61(9):613–637.

[6] Wright, Hamilton (1927). “Plans to Drive Car from Miami to Key West,” Springfield (MA) Sunday Union and Republican, December 11, p.1A.

[7] The account of the drive presented here is compiled from reports published in the Key West Citizen on December 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24, 1927, as well as a story by eyewitness journalist Hamilton M. Wright, “First Motorcar to Reach Key West Under Own Power,” published in the Springfield (MA) Sunday Union and Republican, January 15, 1928, p.7G.

[8] “No less than nine motion picture men were there,” wrote journalist Hamilton M. Wright. Unfortunately, none of their film footage has been located.

[9] Anonymous (1928). “LaSalle Makes Dangerous Trip to Key West, Fla.” Seattle Daily Times, January 22, p.38.

[10] AECOM (2023). 2023 US1 Arterial Travel Time and Delay Study, Monroe County, Florida. For Monroe County Board of County Commissioners.

IMAGES:

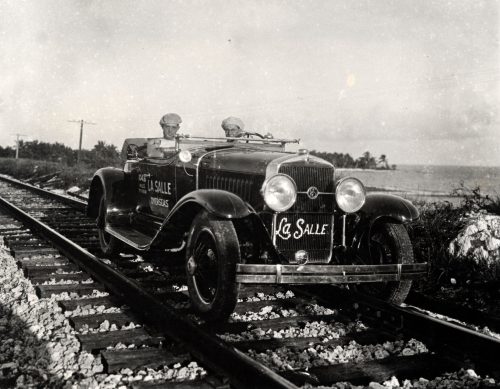

Claude Nolan and Kenneth Goodson on the railroad track on Long Key, as they drove the first automobile to Key West in 1927. Gift of A. Perez. Florida Keys History Center.

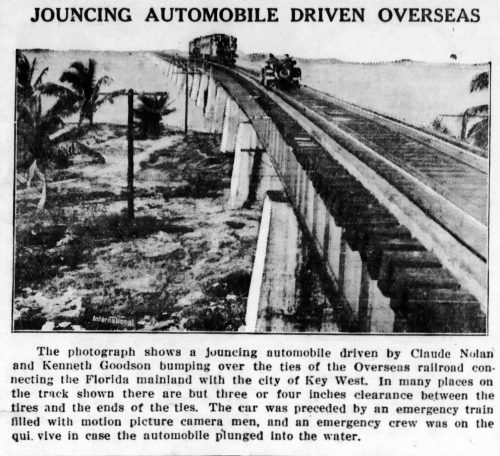

The Centre Reporter, Centre Hall, PA, February 16, 1928, p 7.

You can sign up to receive Island Chronicles from the Florida Keys History Center as a newsletter in your email at this link. We will never sell your email address and unsubscribing is easy with one click.

Looking to catch up on other volumes of Island Chronicles? You can find them here.